This poultry farm saved me from the worries of life

Zakira lives in the Wali Aser region of Mazar-e-Sharif city with her five children — two sons and three daughters. Mazar-e-Sharif is currently experiencing crisis levels food insecurity, with thousands of families struggling to get by. Zakira’s husband died two years ago, after contracting Covid-19, leaving her the family’s sole breadwinner.

lives in the Wali Aser region of Mazar-e-Sharif city with her five children — two sons and three daughters. Mazar-e-Sharif is currently experiencing crisis levels food insecurity, with thousands of families struggling to get by. Zakira’s husband died two years ago, after contracting Covid-19, leaving her the family’s sole breadwinner.

Last year Zakira joined a Hand in Hand Self-Help Group named Hadaf, along with a group of local women. She received business skills training from their female group leader as well as specific training on layer poultry farming. This included nutrition and feed formulation, and how to find a market for her eggs. After her training was complete, and armed with her first business plan, Zakira received a ‘start up kit’ of layer chickens, feed and a chicken coop.

Zakira has now increased her flock to 34 chickens, and can produce around 20 eggs a day. She earns AFN 6,000 (USD 67) a month selling her eggs at the local market. As eggs are a valuable source of protein Zakira knows she will always be able to give her children a nutritious meal.

Zakira says, “I and my children often slept with an empty stomach, but this poultry farm which I started with support from Hand in Hand Afghanistan saved me a lot from the worries of life and made me very comfortable.

“This small business brought a lot of changes in my life, such as having enough food for my children, providing clothes and school stationery and meeting our basic household needs. This is a huge happiness for us. I am now hopeful for a better future for me and my children. I wish to become a businesswoman in the future and expend my business by raising both layer and broiler chickens.”

Meet Zahra, the Hand in Hand trainer fighting Covid-19

When Zahra started working for Hand in Hand six months ago, the 25-year-old thought she’d be training women to run their own micro-businesses, helping them thrive in the long term. Now, as the country braces for a Covid-19 crisis some experts fear could be globally significant, Hand in Hand’s youngest trainer finds herself fighting for their short-term survival instead.

“It’s a very heavy responsibility and we feel a sense of fear. If someone has the virus, it’s difficult to control it,” says Zahra. “On the other hand, it’s a pleasure to help our people, who are really in need and live in poverty.”

Across Hand in Hand Afghanistan the story is the same, as the entire organisation retools – seemingly overnight – to respond to the threat of the virus. Between thousands of members living in hard-to-reach areas, deep bonds with local officials, and a senior management team with decades of humanitarian experience, Hand in Hand Afghanistan is uniquely well-suited to help. So when a government lockdown caused the suspension of our usual training on 30 March, we were ready to adapt and keep fighting.

Phase One of Hand in Hand Afghanistan’s Covid-19 Emergency Response kicks into gear on 5 April, as teams fan out across Parwan, Balkh and Herat Provinces delivering soap, chlorine solution and virus prevention training to some 26,000 people. Fundraising for Phase 2, where we hope to at least double that number, is underway now.

“We consider it our duty to inform people about methods of prevention. We can save lives,” says Zahra. “I had dozens of members who weren’t aware about the coronavirus and how to reduce the risk of infection until I told them.”

Handwashing time for Sharifa and family.

Sharifa, 24, was one of them.

“Zahra told us about coronavirus and how dangerous it is,” says the mother of four young children. “She gave me and other women health instructions such as not to go to crowded places; to wash our hands repeatedly with soap many times throughout the day; to use a mask and gloves, which we have for our poultry farm, if we go out in public; and to cover our mouths with a cloth when we sneeze.”

With no health services in the area, Zahra worries that Hand in Hand’s is the only help Sharifa and thousands more like her will get. “And even if they can make it to the public hospital in Mazar, we know their capacity is very low. They don’t have the equipment to cope,” she says.

One day, Covid-19 will pass – a global health crisis leaving a global economic crisis in its wake. When that day comes, Hand in Hand will be ready to help our members work their own way out of poverty, the same we have since Day One. Until then, we’re fighting Covid-19 with everything we’ve got.

“The second thing I worry about right now is the financial aspect,” says Sharifa. “The first thing is our health.”

By the numbers

4,000 households reached

26,000 Afghans provided with soap and chlorine solution

20 minutes of virus prevention training per household

‘Life was getting worse by the day’: Rozi Khal

Rozi Khal was 13 years old when her first-born son, almost a newborn, was injured in the Soviet-Afghan War. The incident sent her packing for Pakistan, and the heaving refugee camp her family would call home for the next 27 years.

“We didn’t have anything. My husband worked as labourer in Queta city doing very tough work which made him sick. Now he can hardly move,” says Rozi Khal, now 45. “We returned to Afghanistan five years ago. Life was getting worse by the day. until Hand in Hand Afghanistan arrived in our village.”

Qaleen Bafan, Afghanistan

Afghanistan’s displacement crisis

Rozi Khal’s cicumstance is far from unique. Between returning refugees like her and the multitudes of people displaced within Afghanistan by drought and conflict, some 3.5 million Afghans have forced to relocate in recent years – the equivalent, in sheer scale, of the entire population of California being displaced within the US. This in a country with none of the wealth or infrastructure that other countries take for granted.

Rozi Khal’s cicumstance is far from unique. Between returning refugees like her and the multitudes of people displaced within Afghanistan by drought and conflict, some 3.5 million Afghans have forced to relocate in recent years – the equivalent, in sheer scale, of the entire population of California being displaced within the US. This in a country with none of the wealth or infrastructure that other countries take for granted.

In September 2017, Hand in Hand partnered with Deutsche Gesellschaft für Internationale Zusammenarbeit (GIZ), the German government’s development agency, to help displaced Afghans work their way towards a prosperous future in the country’s growing poultry value chain. By summer 2020, we’ll have helped 4,250 of them launch their own sustainable poultry farms.

Afghanistan’s poultry value chain is ideal for returnees and internally displaced people. Skills are easily learned. Incomes, compared to other rural sectors, are high. And for people like Rozi Khal, the benefits don’t end there. Poultry farms can be run from entrepreneurs’ own households – crucial for members with restricted mobility. At the same time, nutrition and food security improve – a matter of particular interest to those responsible for childcare.

A bright future

Rozi Khal holds her daughter.

One day, Rozi Khal received a knock at her door. It was a Hand in Hand trainer: would she like to become a member? Rozi Khal joined a Self-Help Group in Qaleen Bafan village, Balkh Province, and received poultry vocational skills training. Next, she built a backyard poultry farm with the support and guidance of her Hand in Hand trainer. “I never had a business idea until I learnt in training that I can have a business in my home,” says the mother of seven. “The poultry enterprise enables me to earn a decent income and help my family.”

With her training complete and chicken coop built, Rozi Khal received 25 chickens, two bags of feed and some other materials she would need to launch her business. Today, she produces 20 eggs a day, earning approximately AFN 2,400 (US $32) a month.

“Now I’m earning more than I used to working in a brickmaking factory, which was very difficult work,” she says. “The training and support I received from Hand in Hand has encouraged me to start the enterprise and now I am confident I will generate a good income.”

As for the future? “I am planning to expand my enterprise within the coming months to increase my brood because there is a good market for eggs,” she says.

By the numbers

Producing 140 eggs a week

Earning AFN 2,400 (US $32) a month

Caring for family of 9

Meet Mahgul, who hatched a plan after her forced relocation

To Mahgul, Pakistan was home. It was where she was born to parents who sought refuge from the Soviet-Afghan War in the late 1980s. It was where she met the man who became her husband and where she gave birth to her first two children.

That all changed nine years ago when the Pakistani government destroyed the refugee camp where she and her family had been living. They were forced over the border to Mahgul’s parents’ homeland, from where the government assumed she had come.

“We didn’t know anything about Afghanistan except that our families were originally from there,” Mahgul said. “We were forced to leave Pakistan and came to Afghanistan, but we didn’t have anything here: no home, no family and no relatives.”

Mahgul and her family were forced to start anew, and now, with help from Hand in Hand, their once-dim future is shining bright. Not only has she settled into her new home in Balkh province, she has learned how to raise chickens, earning an income that has helped support her family.

Balkh Province, Afghanistan

A continuing crisis

Three million people arrived on Europe’s shores hungry and desperate for work during the migrant crisis of 2015-16. Imagine, however, if more than 50 million people had arrived instead, and that Europe was one of the most impoverished places on earth, lacking not only the ability to house those who arrived but also the ability to care for and support them.

That, proportionally, is the problem facing Afghanistan, which has seen millions of people flee their homes over the past three decades because of conflict. More than 2.5 million people are expected to arrive in the country over the next two years from places such as Pakistan and Iran, even as another 1.8 million internally displaced people (IDPs) settle elsewhere in the country to escape intensified conflict.

Establishing a home

Mahgul and her family spent more than a year in Afghanistan living in a tent before they, and other migrants, were taught by the UN Refugee Agency how to build shelter. Mahgul’s husband found work as a shopkeeper, and they settled into their new lives in the village of Mahajir Qeshlaq, in the Sholgara district of Balkh province.

But for Mahgul, now 30, the desire to continue to make a better future for her family remained strong. Last year, she learned about Hand in Hand Afghanistan and, excited by the prospect of earning an income, joined the programme to learn the basics of poultry farming.

Over five days, Mahgul learned not only how to properly raise and care for chickens, but also how to run and develop a business and manage her finances. At the end of her training, she received her own chickens, as well as feed and a number of tools, as part of an enterprise start-up kit designed to help her succeed.

Forging a future

Not even a year into her new endeavour, Mahgul’s farm has grown to include 32 chickens that produce an average of 20 eggs each day. Though some are kept to help feed her family, she sells most of them, earning a monthly income of nearly 3,000 AFN (US $40).

That income has not only helped her support her family, but it has also allowed her to help put her children through school.

Less than a decade ago, Mahgul was left helpless as she and her family were forcibly deported from her home. Now, she has not only been empowered to forge her own future, but she has cultivated one for her children as well.

Mahgul’s results

Settled after forced relocation to Afghanistan

Increased monthly income from 0 to 3,000 AFN (US $40)

Able to contribute to school fees for her children

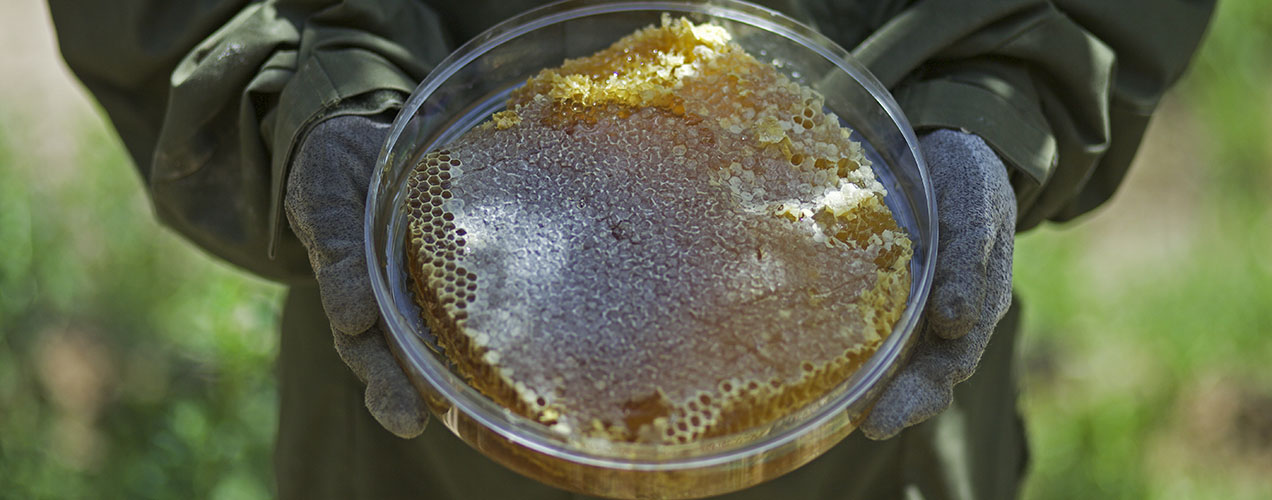

Meet Frozan, who has created a buzz around Marmul

Frozan, 18, lives in north Afghanistan, a corner of the world where opportunity is scarce. Still, that never stopped her from dreaming. “We are a big family and my father, a farmer, was the only one earning – it was never enough. I have always wanted to do something to help but I didn’t know how.”

Didn’t, that is, until she met Hand in Hand. Frozan joined a Self-Help Group and quickly became a star pupil. Training led to a business plan, which led to a loan from fellow group members. Finally, she was ready: the newest and youngest beekeeper in her village. Her business has not only helped put her through school, but it has done the same for her younger siblings and even helped her parents provide for the family.

Mazar-i-Sharif, Balkh Province, Afghanistan

Keeping busy

As a student, Frozan had already achieved more than her peers, but a desire to help her family would not let her stop there.

After joining the Shogufa SHG, Frozan attended regular meetings and supplemented her schoolwork with training on microfinance, bookkeeping and business development.

“I was keen to have a business from the first group meeting until I completed [business development] training, when I understood how to run a business and what I should consider before starting a business,” Frozan said. “Therefore, with the help of my trainer, I developed a business plan.”

Frozan carried out a study of the Marmul district in the Balkh province in northern Afghanistan and learnt that there was a high demand for honey. After further research, she discovered that beekeeping doesn’t require much labour – a perfect arrangement for a full-time student – and so she applied for and obtained a microloan of 10,000 afghanis (US $140) so that she could purchase two boxes of bees.

Sweet success

As the youngest person in Marmul to keep bees, the SHG taught Frozan the skills she needed to look after them, as well as how to extract the honey and improve its quality and volume.

After her first year, she had harvested 16 kg (35 lbs) of honey, making enough to not only repay the microloan but to leave her with a small profit. She invested that back into her business by buying more bees, and last year, she earned 120,000 afghanis ($1,728) from the 120 kg (265 lbs) of honey produced by a collection of what had grown to 20 beehives.

“After first year of my business, I was amazed to see the results,” Frozan said. “I repaid the loan and expanded my business. Now I am paying school expenses of my two younger siblings, helping my dad in home expenses and I have my own savings for emergencies.”

Frozan’s classmates have told her they have been inspired by her business and that they would like to set up their own.

“People having a business like me can help their families to overcome financial challenges, save for emergencies and take active part in developing economy of their communities,” she said.

“Now I have learnt how to manage my activities and time, and work confidently in order to improve our lives. I am also saving for expanding my business, which will in turn generate more income for me in the future.”

Frozan’s results

Increased monthly income from 0 to 10,000 AFN (US $144)

Able to contribute to school fees for her siblings

Inspired classmates to create their own businesses

Meet Zubaida, the ‘famous’ tailor from Marmul district

Four years ago, Zubaida had no job and no income. Today, she’s something of a local celebrity, “famous” for running her own tailoring business. With her newfound income, the 32-year-old is feeding her children a more nutritional diet. And with her growing reputation, she’s training six people in her community to work as tailors, just like her.

The Gul Lala Self-Help Group

Employment in Afghanistan is hard to come by. Poverty is not. Some 39 percent of Afghans live on less than US $1.90 a day, the World Bank’s threshold for ‘extreme poverty’.

Zubaida used to be one of them. Back in 2014, she was struggling to feed her five children with her family’s monthly income of AFN 7,000 (US $100). So when Hand in Hand Afghanistan offered her the chance to learn business skills as part of a Self-Help Group, she leapt at the chance.

Hand in Hand’s budding entrepreneurs are offered the chance to learn basic business skills, form a community and build a pool of savings that can be used to take their initiatives further. Zubaida joined the Gul Lala Self-Help Group and did exactly that, taking an initial loan of AFN 10,000 (US $200) to establish her own tailoring business after gaining the training and confidence she needed.

Entrepreneurial pursuits

Zubaida serves her daughter lunch

Today, Zubaida designs, makes and sells women’s clothes for AFN 200 to 450 (US $3 to $7) an item, while the clothes she makes for children fetch AFN 150 to 200 (US $2 to $3). Between them, she earns about AFN 6,000 (US $85) a month.

But the impact of her new enterprise isn’t only financial. “Now I’m able to make decisions about my kids and describe my views and opinions in a better way with my family members,” she says.

And her sense of empowerment doesn’t stop there. “My neighbours and relatives see me as a businessperson and as an instructor, which makes me proud,” says Zubaida. “My enterprise has made me famous and it has given me the courage to take part in social activities.”

Having paid her loan back to the group, she is now training six people like her in tailoring entrepreneurship. Not only has her business allowed her to build financial freedom and confidence, it has given her a platform to train and inspire others to improve their own lives.

Zubaida’s results

Monthly income: AFN 6,000 (US $100)

Training six members of her community

Feeding her five children healthier meals

Meet Saboor, the young father who saved his family’s fortunes

Walk a mile in Saboor’s shoes and you’ll know his struggle.

No, really.

Fed up with being chronically underemployed – “It’s hard to find employers who pay regular wages,” he explains – the 28-year-old husband and father had dreams of launching his own shoe business, but for years, they remained just that. When the growling in his 4- and 2-year-old’s stomachs became too loud to bear, Saboor resolved to move his family out of Afghanistan. Anywhere, he remembers thinking, would be better than this.

Then he caught wind of an NGO that was training local people to run their own businesses and, suddenly, home didn’t seem so bad.

Mazar-i-Sharif, Balkh Province, Afghanistan

Afghanistan’s quiet crisis

Imagine if during the 2015-’16 migrant crisis some 50 million people, not 3 million, arrived on Europe’s shores, hungry and desperate for work. Now imagine if Europe was one of the poorest places on Earth, lacking even the most basic services required to keep up.

That, proportionately, is the problem facing Afghanistan, the world’s largest source of refugees for more than three decades. Today, Asia’s poorest country faces the inverse problem: the world’s largest returnee crisis, with some 2.5 million people expected back in the country this year and next, chased across the Pakistan border by new visa requirements, increased police raids and deportations, and a lack of employment opportunities, according to the UN.

Afghanistan’s returning millions need access to housing, education, clean water and healthy food. In short, they need jobs. In some cases, Hand in Hand is working directly with this growing cohort, particularly around the country’s growing poultry value chain. But the scale of the crisis means all of our programmes have taken on new importance.

Where will returnees get jobs if not from employers?

A shoe-in for success

Saboor

Materials, margins, marketing – Saboor learned a lot from his Hand in Hand trainer. “I am so thankful for the support and guidance,” he says. Today, his Noman Subhan brand shoes and sandals are all the rage in the markets and stalls of Mazar-i-Sharif, Afghanistan’s second-biggest city.

Quality, of course, will cost you – precisely AFN 625 (US $9) a pair. Multiply Saboor’s mark-up of AFN 135 (US $2) per pair by roughly 145 pairs a month and the Phil Knight of Mazar-i-Sharif is making 19,575 AFN (US $285) a month in pure profit. It’s enough to make sure his children are well-fed, sheltered and educated. Enough to make his wife proud. Enough to fuel realistic ambitions of international sales in neighbouring Uzbekistan. And enough employ six of his neighbours.

All of them, he adds, earn a regular wage.

Saboor’s results

Average monthly business income: 19,575 AFN (US $285)

Number of employees: 6

Better health and education for his children

Meet Mushtary, Rejin’s first female shop owner

Mushtary is breaking new ground as a shopkeeper and entrepreneur in the rural village of Rejin, Afghanistan.

A shop to stave off hunger

Mushtary’s shop |Products on shelf | Balk province, Afghanistan

The regular profits from her business enable her to supplement the small and variable income the family gets from farming. “Farming in our area is risky because we rely on the rain and if the weather is not right then we lose everything. The shop means that even in the bad times we can buy food to eat.”

Initially Mushtary and her neighbours joined the Self-Help Group set up by Hand in Hand Afghanistan in their village out of curiosity but quickly realised that there was so much they could learn. Together the group of 20 members began saving a little money each week to build up a group savings fund and learnt basic business skills such as bookkeeping.

Historically the people in Rejin village are farmers, so the majority of the members in the group decided to use their new skills to branch out into animal husbandry. Mushtary had other ideas. She and her husband had struggled for many years to support their family on the income from farming but they could not rely on this income. Everything depended on the weather. Mushtary saw an opportunity to stabilise the family income.

Rejin’s first retailer

Rejin is an isolated rural village. Women have to travel long distances to buy everyday household items and Mushtary realised that if there was a shop in the village, local people would chose to buy what they needed here. So, Mushtary borrowed from the group fund in order to buy her initial stock of clothes. These sold so well that Mushtary made a profit of AFN 5,000 (US $96). From this small beginning she went on to borrow a further AFN 10,000 (US $192) and has now opened a shop selling tea, sugar, biscuits, chewing gum, shampoo, washing up liquid, soap and many more necessary items.

“Even in the bad times we can buy food to eat”

Feroza, the 22-year-old mother with plans to expand her enterprise

Feroza was one step ahead of Hand in Hand when we arrived in Balkh, the north Afghanistan province she calls home. At 22, she already earned a small income tailoring clothes for her neighbours. Still, even by the modest standards of her small village, money was tight. So when she heard Hand in Hand was offering business training she jumped at the chance.

Since then her income has quadrupled, bringing the new mother off subsistence wages and elevating her status at home and in the community.

Balkh province, Afghanistan

Tailored market research

“Before (joining a Self-Help Group) I didn’t know about market surveys or pricing,” says Feroza, putting the finishing touches on an ornate red shawl as her daughter looks on. “I’ve also started sewing seasonal products and selling at the markets in Mazar-i-Sharif (the closest major city). It’s made a huge difference; I now earn 3,775AFN (US $68) a month.”

“My new income means I can support my children the way I think is best, without waiting for anyone’s approval”

Future sewn up

Afghanistan’s child mortality rate is the highest outside sub-Saharan Africa: 99 out of every 1,000 children die before turning 5. (In Sweden, as a point of comparison, that number is 3 per 1,000.) Education, though improving, has historically been rare.

Still, Feroza has every reason to be hopeful about her children’s future. Besides enabling her to buy more nutritious food, a growing income will help pay for crucial healthcare to protect them from illness, and school supplies when she gets older.

Still, Feroza has every reason to be hopeful about her children’s future. Besides enabling her to buy more nutritious food, a growing income will help pay for crucial healthcare to protect them from illness, and school supplies when she gets older.

“My new income means I can support my children the way I think is best, without waiting for anyone’s approval,” she says. It’s no surprise.

And that’s not the only benefit for the future. To meet the growing demand for the bedding and clothes she tailors, Feroza has taken on three young people from her village as apprentices, some of them mothers themselves. Each earns a share of the income from the pieces they sew, and all have plans to become fully-fledged tailors.

Ever the entrepreneur, Feroza has no intention of stopping there. “I plan to expand my enterprise, hire and train more people, increase my production and target new clients,” she says.

Feroza’s results

![]()

Monthly earnings 3,775 AFN (US $68)

![]()

Able to provide healthcare, nutritious food and education for her children

![]()

Hired three apprentices from local community

Meet Najia, Nahri Shahi district’s most canny businesswoman

Najia is a canny entrepreneur in more ways than one. Armed with nothing but her wits and the skills she learned at a Hand in Hand Afghanistan Self-Help Group, the mother of four increased her income from zero to 40,000AFN (US $720) a month – all by selling canned goods.

Financial success has of course been rewarding, says Najia, who like most Afghans has no surname. But a newfound sense of empowerment makes the long, often gruelling hours especially worthwhile. “My life has totally changed,” she says. “I’m no longer dependent on anyone else’s income and I can easily purchase clothes and school materials and take my children to the doctor. I’m even saving for emergencies – and to expand my enterprise.”

Loans, not grants

Like any budding entrepreneur, Najia needed credit. There was just one problem: she didn’t qualify, not even for a microloan. Self-Help Groups offer members the opportunity to learn, to develop opportunities, even simply to socialise outside the home. They also offer access to group savings funds, available to members who’ve paid in and undergone training. As soon as she was ready, Najia applied for a loan using a strategy every bit as simple as it was effective: serving her food to group members and letting it do the talking. The group was convinced; Najia got her loan.

“I had the talent,” she says, “but I didn’t know the basics of enterprise. Hand in Hand Afghanistan mentors helped me establish myself, both in terms of training and funding.”

“My life has totally changed. I’m no longer dependent on anyone else’s income and I can easily purchase clothes and school materials and take my children to the doctor”

Najia secured two loans – 21,000AFN (US $378) from her group then 10,000AFN (US $180) from Hand in Hand, both now paid off. The first went to setting up her operation, the second to diversifying her product range.

“We prepare cans of pre-cooked meals with ingredients including okra, eggplant, peas, noodles and meat. I also make ketchup and jam,” she explains. “My meals are good quality and I supply them to the market quickly.”

Super markets

Starting out, Najia sold her food in neighbouring villages. Drawing on the lessons she’d learned about market linkages, she soon moved into Mazar-i Sharif. Then came her biggest success yet: a deal supplying food to the Ariana Supermarket.

Today, Najia has 18 part-time staff. She hopes to hire them full-time soon. “We plan to establish a small food product manufacturing plant with modern labelling machines to compete with imported cans,” she says.

Building confidence

Impressive as it is, Najia’s success is not unique. According to a recent independent review commissioned by the Swedish International Development Cooperation Agency (Sida), Afghans are reaping the benefits of Hand in Hand’s programmes, citing the value of training and savings, as well as a newfound freedom of movement. Others meanwhile credited interaction among group members with instilling a new sense of self-confidence. Not surprisingly, Najia was among them.

Impressive as it is, Najia’s success is not unique. According to a recent independent review commissioned by the Swedish International Development Cooperation Agency (Sida), Afghans are reaping the benefits of Hand in Hand’s programmes, citing the value of training and savings, as well as a newfound freedom of movement. Others meanwhile credited interaction among group members with instilling a new sense of self-confidence. Not surprisingly, Najia was among them.

“I feel happy I decided to start my own business,” she says. “And confident to expand it.”

Najia’s results

![]()

Increased monthly income from 0 to 40,000 AFN (US $720)

![]()

Expanded business to other districts and local supermarkets

![]()

Employed 19 part-time staff