‘I want to be a real entrepreneur’: Anita

Take the road out of Arusha in the foothills of Mount Neru. Head south to Olkeriani and keep going until you hit the edge of town. Keep moving past the end of the tarmac, past the last of the cinderblock homes, and arrive at a building made from sticks and plastered with mud. Look for the woman with a lifetime in her eyes.

Anita Msele has been up since 5am, when she rose to make maize and chai tea for her sons. Aged 41, and with a full day’s labour ahead of her, she passed on the maize. “I think of the boys and I can’t eat,” she says. “I can’t let them go to school hungry.” It’s nearly midday.

Outside under a soil-thumping sun, young patches of maize, spinach and sugarcane struggle towards harvest, still months away. Inside, Anita’s young tailoring business also struggles to get off the ground. It was the same story last year when she tried selling socks at the market, and the year before that selling shoes, second-hand, door-to-door.

Anita feeds you tea with sugar, and when you ask her what worries her, leads you outside and pokes at her home’s foundations. A small piece comes crumbling to the ground. The home was built in 2005, she says, the same year her husband died. “At night in the wind and the rain the roof leaks and the house moves. We can’t sleep – it could fall down at any moment.”

Olkeriani, Tanzania

Gathering shadows

Anita outside the family home.

Anita is not hungry by choice. She is trying her hardest – and doing an incredible job – in a world that treats her as surplus and a climate that’s hostile to her survival. Like every one of us, she needs help.

Nine percent of households in and around Olkeriani earn their income solely from business – owning a shop, for example, or transporting people or goods on boda bodas (motorcycle taxis). Fifteen percent earn some of their income from business. The rest, 76 percent, rely entirely on farming to see them through, many at the subsistence level. And time’s not on their side.

Rainy and dry seasons cause boom-and-bust crop cycles: little followed by less followed by none. As the climate worsens, those cycles are becoming harder to predict and almost impossible to manage. For the 55 percent of Anita’s neighbours who live below the poverty line, the need to adopt climate-resilient farming practices and diversify sources of income is dire – and exactly where Hand in Hand aims to help.

A path to success

Anita sewing at home.

When Anita joined her Self-Help Group three months ago it wasn’t the lure of income that sold her but the promise of companionship. Still, as the training the progressed, she began to feel a glimmer of (was it?) hope.

“The training’s been mind-opening. I understand now about buying and selling. I understand about saving some of the money I earn,” says Anita.

“I want to get out of this situation where I have to beg for everything. I want the children to go to school so that they can achieve their goals. I want to be a real entrepreneur. So I will stick with Hand in Hand.”

With the dry season looming, she still has a long way to go. But for the first time in a long time – down the road from Arusha, at the edge of Olkeriani, past the end of the tarmac, near the cinderblock homes – the distance doesn’t seem too far.

By the numbers

Rural adult population living in poverty in Hand in Hand’s target areas: 293,110

Number of jobs we aim to create: 200,000

Percentage of target rural poor with improved incomes: 68 percent

‘I will be ending poverty’: Jamleck, a farmer transforming Kenya

Jamleck Laska Arume is hoping he holds the solution for the droughts that have affected millions of Kenyans.

A 28-year-old farmer whose family owns seven acres of land in Embu County, Jamleck has planted banana trees that agronomists believe will be less susceptible to climate shocks.

It’s an especially exciting proposition because the drought wiped out nearly his entire maize harvest last year. Now part of Hand in Hand’s push to help more than 40,000 farmers stand up to climate change, Jamleck had to shoulder the additional expense of pumping water to the farm.

Even then, he was left with barely enough maize, notoriously vulnerable to climate variability, to provide for his own family.

“We didn’t have anything,” he said. “Like, specifically, we used maize for what we use in the house. These bananas, we are using them as a business. We can use them to earn money.”

Embu County, Kenya

New crops, new future

Kenya’s National Drought Management Agency now believes that droughts will distress the region every five or so years. More than three quarters of the country has been affected by the most recent devastation, and even those counties that have recovered are still experiencing severe vegetation deficit. Livestock, and not just crops, has also been lost.

An estimated 14 million people in Kenya can’t meet daily food requirements, according to research from Kenya’s Egerton University, and 4 million couldn’t even meet their daily calorific requirements if they spent their entire incomes on food. Almost all of these people are rural.

Bananas are one of the most prevalent crops grown throughout Kenya, but, like maize, they’re also highly susceptible to diseases and moderate changes in climate. By adopting techniques and farming what are known as tissue culture bananas, which are more resistant, can produce higher yields and grow much faster, they can help mitigate drought-stricken areas like Embu County.

That’s why Jamleck has volunteered to plant them. Not only is his family’s farm large enough, he has never grown bananas — an important characteristic to making sure the tissue culture bananas thrive because the land will not have been previously affected by disease.

Hand in Hand, with the support of the IKEA Foundation, will continue to help Jamleck with growing the bananas on his “demo farm,” providing him with the tools and instruction he needs to make sure they succeed. Once they’re ready, he and others in the community will be brought together to negotiate with wholesalers to distribute the bananas around the country.

All told, Jamleck will be one of more than 43,000 smallholder farmers who will have increased their incomes while helping thousands of communities address issues they face directly as the result of climate change.

“I feel it’s just what I need,” Jamleck said. “What I have been learning in the community will be ending poverty, so what I need is to help others so they can also learn from me.”

A bright future

Jamleck’s interactions with Hand in Hand haven’t been limited to planting bananas. He has also learned a lot about the fundamentals of running a business, including the process of learning how to manage profit, and has begun to recognise there are ways he can increase his margins.

“They didn’t tell us they would give us anything, but they showed us,” he said. “They want to make us stand by ourselves. They want us to be able to do more things by ourselves so we can produce and we can accomplish more things.”

Thus far, Jamleck has been able to purchase his own water pump to help irrigate his crops, and he wants to buy additional cows to better fertilise the farm. His next step will be to hire people who can help him with the farm, not only to plant and harvest the crops but also to take the coffee beans to be sold and processed at local factories.

And, because he regrets that his parents were not able to pay for him to have a proper education, his ultimate goal is to make enough money to be able to do so for his 2-year-old daughter, Blessings.

Should the banana crop succeed, Jamleck will not only have provided her with a future but will have done so for countless of people across Kenya as well.

Planted resistant banana crop to mitigate drought effects

Purchased water pump with profit from existing maize and coffee crops

Developing plans to continue expanding business

‘Life was getting worse by the day’: Rozi Khal

Rozi Khal was 13 years old when her first-born son, almost a newborn, was injured in the Soviet-Afghan War. The incident sent her packing for Pakistan, and the heaving refugee camp her family would call home for the next 27 years.

“We didn’t have anything. My husband worked as labourer in Queta city doing very tough work which made him sick. Now he can hardly move,” says Rozi Khal, now 45. “We returned to Afghanistan five years ago. Life was getting worse by the day. until Hand in Hand Afghanistan arrived in our village.”

Qaleen Bafan, Afghanistan

Afghanistan’s displacement crisis

Rozi Khal’s cicumstance is far from unique. Between returning refugees like her and the multitudes of people displaced within Afghanistan by drought and conflict, some 3.5 million Afghans have forced to relocate in recent years – the equivalent, in sheer scale, of the entire population of California being displaced within the US. This in a country with none of the wealth or infrastructure that other countries take for granted.

Rozi Khal’s cicumstance is far from unique. Between returning refugees like her and the multitudes of people displaced within Afghanistan by drought and conflict, some 3.5 million Afghans have forced to relocate in recent years – the equivalent, in sheer scale, of the entire population of California being displaced within the US. This in a country with none of the wealth or infrastructure that other countries take for granted.

In September 2017, Hand in Hand partnered with Deutsche Gesellschaft für Internationale Zusammenarbeit (GIZ), the German government’s development agency, to help displaced Afghans work their way towards a prosperous future in the country’s growing poultry value chain. By summer 2020, we’ll have helped 4,250 of them launch their own sustainable poultry farms.

Afghanistan’s poultry value chain is ideal for returnees and internally displaced people. Skills are easily learned. Incomes, compared to other rural sectors, are high. And for people like Rozi Khal, the benefits don’t end there. Poultry farms can be run from entrepreneurs’ own households – crucial for members with restricted mobility. At the same time, nutrition and food security improve – a matter of particular interest to those responsible for childcare.

A bright future

Rozi Khal holds her daughter.

One day, Rozi Khal received a knock at her door. It was a Hand in Hand trainer: would she like to become a member? Rozi Khal joined a Self-Help Group in Qaleen Bafan village, Balkh Province, and received poultry vocational skills training. Next, she built a backyard poultry farm with the support and guidance of her Hand in Hand trainer. “I never had a business idea until I learnt in training that I can have a business in my home,” says the mother of seven. “The poultry enterprise enables me to earn a decent income and help my family.”

With her training complete and chicken coop built, Rozi Khal received 25 chickens, two bags of feed and some other materials she would need to launch her business. Today, she produces 20 eggs a day, earning approximately AFN 2,400 (US $32) a month.

“Now I’m earning more than I used to working in a brickmaking factory, which was very difficult work,” she says. “The training and support I received from Hand in Hand has encouraged me to start the enterprise and now I am confident I will generate a good income.”

As for the future? “I am planning to expand my enterprise within the coming months to increase my brood because there is a good market for eggs,” she says.

By the numbers

Producing 140 eggs a week

Earning AFN 2,400 (US $32) a month

Caring for family of 9

‘I now feel good because I have money’: Roseline, chip vendor

Even though she recognised the importance of providing her children with an education, Roseline Ngeno hurt every time she had to pay their school fees. The salary her husband made as a teacher only went so far, and because the tuition was a priority, the family often struggled to meet basic needs.

That all changed once Roseline, 40, joined a Hand in Hand Self-Help Group generously supported by the IKEA Foundation. Empowered with the knowledge of how to run a business, she has been growing potatoes and selling chips that residents of her village of Molem, in the ward of Merigi in Kenya’s Bomet East sub-county, can’t stop eating.

“I now feel good because I have money,” Roseline says. “I have no worries. When my children want clothing, I have money. If I want to plant in the garden, I have money. I calculate my profits and I keep them and use them well.”

Bomet County, Kenya

A difficult path

Women living in Bomet county such as Roseline have a hard time finding permanent employment. As she says, “Women don’t have a chance of getting jobs here.”

The Kenya Red Cross Society determined in a 2015 study that 42.9 percent of households in Bomet County earn less than US $3.20 a day. Only 34 percent of women in the county aged 15-49 have at least some secondary school education, according to a 2014 report by Kenya’s National Bureau of Statistics.

Bomet is one of the most densely populated areas in western Kenya and, with 58,000 registered farmers, its economy leans heavily on agriculture. Even then, very few are women, as most tend to the home and the cattle, and almost none hold permanent jobs.

Chipping away boundaries

Roseline, who had occasionally earned a temporary income in the past, knew she needed to do something to help brighten the futures of her seven children. Through a friend, she heard about Hand in Hand’s Kondametutab Molem Self-Help Group in 2016 and joined, hoping to learn a thing or two about ways she could start her own business.

“I used to find it difficult asking my husband for money all the time, and when he said there is no money, I felt bad,” Roseline says. “But now, since I joined the group, I’ve been able to make money quickly.”

Having been taught the basics of bookkeeping, entrepreneurship and table banking, Roseline was able to access the land leased by the group. She then realised no one else was growing potatoes, and after thinking of a way to sell them to the rest of the community, she decided to turn them into chips.

Achieving that miraculous balance of crispy and unctuous, Roseline’s chips are a revelation – superior, 10 times out of 10, to the stodge at your local chippy.

Roseline, who also sells tea and chapatis, offers the chips for KES 30 (US $0.30) or KES 50 (US $0.50), often to schoolchildren. While it helps that she doesn’t have any competition, finding the right recipe has kept villagers coming back for more.

“If you want to make good chips, you chop potatoes first, put the right amount of oil in the pot and cook them until they are dry — but not too dry,” Roseline says. “I prefer chips that are not very dry.”

Growing a future

Since starting her business, Roseline estimated she has been able to make KES 10,000 ($98 USD) a month. She has not only put that money toward her children’s school fees but has reinvested it as well.

“My income has increased very much,” she says. “The business does help me. I have been able to decorate my house and bought some utensils.”

Her goal is to expand the business, as she would like to one day be able to sell sugar and other food to people in the village. And her husband, whose time is limited because he teaches at a primary school far from home, has also helped out.

“I am thankful to God because the [Hand in Hand] donors have enabled me to join the Group that has taught me a lot of things,” Roseline says. “All this has improved my life.”

Roseline’s results

Learned fundamentals of shopkeeping

Able to provide for children’s school fees

Wants to continue to grow business

Meet Richard and Jane: the farmers transforming Kenya

“It’s not much to look at yet,” says Richard Langat, gesturing operatically at an empty dirt field, a twinkle of insane pride in his eyes. “But it will be.”

The 54-year-old farmer and Hand in Hand member has arrived at the edge of his smallholding, a quarter-acre of gently sloping countryside in Bomet County, Kenya, five hours west of Nairobi by SUV on roads so bumpy the four-wheel drive might as well have four legs. He’s been expounding on plants for the better part of an hour.

“All this one needs is a bit of pruning.” “Those? Those are soya beans.” “Insects, birds – they can’t resist capsicums [bell peppers]. That’s why I only grow a few: as a decoy to distract pests from my real crops.”

It’s an encyclopaedic display, one elevated to the miraculous by Richard’s apparent ability to forego breathing completely. But for all the activity on his buzzing farm, it’s this empty field, populated by a lone, straggly seedling not quite as tall as Richard’s old wellies, that’s caught the attention of neighbours and put Richard at the centre of not just his small rural community, but of Hand in Hand’s push to help more than 40,000 farmers stand up to climate change and move from subsistence to success. Far more notable than soya beans and decoy peppers is what’s not here: maize.

Bomet County, Kenya

Out with the old

If you’re in Kenya and you’re eating, you’re eating ugali. Made by boiling maize flour and, if you’ve got the money, enjoyed alongside meat or fish, this stodgy staple with a texture somewhere between polenta and drying cement is less the national dish than a central fact of existence. For millions of subsistence farmers, it’s the only meal they’ll eat all day.

Introduced by the Portuguese in the 17th and 18th centuries, then grown for export under British occupation in the 19th and 20th, the crop shot to ubiquity after colonial landowners discovered it also served a domestic purpose: cheap fuel for farm labourers. To consider the history of maize, in other words, is to consider the history of Kenya itself. But if maize has shaped the country’s past, it cannot shape its future, say experts. Famously vulnerable to ‘climate variability’ – droughts, floods, the vicissitudes of climate change – the crop is putting Kenya’s food security at risk, even while dooming millions of farmers like Richard to a cycle of deepening poverty.

“Since I’ve been here I’ve been trying to make money out of this farm, but I couldn’t,” he says. “When we invest KES 10,000 (US $100) in maize and come away with KES 3,000 (US $30) it’s not even enough to feed our family. We’re really making a big loss.”

For Richard, as for his neighbours, the solution is clear: stop growing maize and start growing something else. That’s easier said than done. Asking most Kenyans to stop growing maize is like asking a Kansan to stop growing wheat, or a shepherd in north Wales to abandon his flock.

Richard isn’t most Kenyans.

Beside every good man

Jane, 47.

Richard met Jane at a funeral. It was love at first sight.

Twenty-six years later the married couple still finish each other’s sentences, still audibly thrum when the other comes near. Richard likes to talk politics. Jane prefers to talk church. But get them going on any of their five children or the farm they’ve built up over the years and the two sing in perfect harmony.

“Before I was given this farm by my parents, the land was really exhausted,” says Jane, 47. “None of my brothers even wanted it, but you can see that it’s fertile now.”

Adds Richard: “The infrastructure around here still needs work, though. Give us roads, give us water – we’ll take care of the rest.”

Throughout Kenya, it’s a similar story. More than a third of the country’s 45 million people can’t afford to meet their basic needs, including food, clothing and shelter, according to research from Kenya’s Egerton University. Fourteen million can’t meet their daily food requirements. And 4 million couldn’t meet their daily caloric requirements if they spent their entire incomes on food. Almost all of these people are rural.

To transform their land from barren to fecund, the Langats have had to take risks and be enterprising. So when Hand in Hand arrived in Bomet County in the summer of 2017 offering a new crop – and new hope for a prosperous future – they jumped at the chance.

In with the new

Question: how do you to convince a community of farmers to abandon centuries of tradition and stop growing the crop they’ve survived off their whole lives?

Answer: you don’t.

Instead, you convince one of them, providing an entirely new crop that’s been selected for profitability and bred to withstand climate shocks like flooding and drought. Next, you throw in a university-trained agronomist to provide expert support. Then you step back and let the results – and the profits – speak for themselves.

So it was when Hand in Hand arrived on the Langats’ farm one sweltering day in the summer of 2017, carrying a basket of curiously tart fruit.

“I wasn’t familiar with passion fruit,” says Richard, holding out what looks like a plum. “Hand in Hand opened our minds. The training was simple and the crop doesn’t need too much attention, but it’s had a really big impact.”

“Big” is an understatement. In less than a year, the Langats went from losing KES 7,000 (US $70) harvesting maize to making KES 15,000 (US $150) each week growing passion fruit. Their neighbours, it will come as no surprise, have been keen to learn more. “Now that they’re seeing it, everybody’s doing it,” says Richard. “So far only two of us are harvesting. Then there are a number who are planting and others who are preparing to plant.”

Richard holds out a passion fruit.

Hand in Hand will be there for each and every one of them, first by propagating the crop using cuttings from Richard’s original, then by providing training on its upkeep and care using the Langats’ plot as our ‘demo farm’. Next year, when they’re ready, we’ll help the community form a producer’s group to negotiate with wholesalers, launching their produce into bigger markets and value chains. And we’re not stopping there.

Throughout Kenya, with generous support from the IKEA Foundation, our model is also propagating, reaching thousands of communities one Richard at a time. By the time we’re one, we’ll have helped more than 43,000 smallholder farmers boost their incomes while standing up to climate change with diversified, resilient crops. The money they earn will reverberate far beyond their smallholdings.

“I’ve got a boy in secondary school, a daughter in university studying French, and another studying computers at the Technical University of Mombasa,” says Richard. “With the money I earn, I’m paying the fees.”

Jane puts it more simply. “Now that we grow passion fruit instead of maize, we can buy our daily meals – not grow them. And when the children come home to visit, they can keep some money. I feel very happy, very loved. It’s a special feeling to know I can give them some money.”

And with the even newer

Richard, 54, his avocado plant and his empty field.

Back to the empty field, and Richard’s lone, straggly plant.

“This is hass avocado,” he says. “I got it from Hand in Hand.”

Kenya’s avocado exports have increased eight-fold since the turn of the century. Last year alone, prices doubled. A byword for Western hipsters, the nutrient-rich fruit is growing in popularity domestically, too. And Richard, and his neighbours, are soon to cash in.

Three years from now, this field and the farms surrounding it will support hundreds of fruit-bearing trees, the Langat’s plot again acting as demo farm, with Hand in Hand again providing support. Even if prices stall, each tree will be worth US $100 a year.

“You can see the way that I’m happy. I didn’t think it would be possible, I didn’t believe. I don’t even know if this is reality or a dream, because happiness comes for me if I just have a small-small profit from my crop,” says Richard, crouching down to get closer.

It’s not much to look at yet. But it will be.

By the numbers

KES 7,000 (US $70) loss growing maize during last harvest

KES 15,000 (US $150) per week growing passion fruit

Putting children through school and university

Meet Mahgul, who hatched a plan after her forced relocation

To Mahgul, Pakistan was home. It was where she was born to parents who sought refuge from the Soviet-Afghan War in the late 1980s. It was where she met the man who became her husband and where she gave birth to her first two children.

That all changed nine years ago when the Pakistani government destroyed the refugee camp where she and her family had been living. They were forced over the border to Mahgul’s parents’ homeland, from where the government assumed she had come.

“We didn’t know anything about Afghanistan except that our families were originally from there,” Mahgul said. “We were forced to leave Pakistan and came to Afghanistan, but we didn’t have anything here: no home, no family and no relatives.”

Mahgul and her family were forced to start anew, and now, with help from Hand in Hand, their once-dim future is shining bright. Not only has she settled into her new home in Balkh province, she has learned how to raise chickens, earning an income that has helped support her family.

Balkh Province, Afghanistan

A continuing crisis

Three million people arrived on Europe’s shores hungry and desperate for work during the migrant crisis of 2015-16. Imagine, however, if more than 50 million people had arrived instead, and that Europe was one of the most impoverished places on earth, lacking not only the ability to house those who arrived but also the ability to care for and support them.

That, proportionally, is the problem facing Afghanistan, which has seen millions of people flee their homes over the past three decades because of conflict. More than 2.5 million people are expected to arrive in the country over the next two years from places such as Pakistan and Iran, even as another 1.8 million internally displaced people (IDPs) settle elsewhere in the country to escape intensified conflict.

Establishing a home

Mahgul and her family spent more than a year in Afghanistan living in a tent before they, and other migrants, were taught by the UN Refugee Agency how to build shelter. Mahgul’s husband found work as a shopkeeper, and they settled into their new lives in the village of Mahajir Qeshlaq, in the Sholgara district of Balkh province.

But for Mahgul, now 30, the desire to continue to make a better future for her family remained strong. Last year, she learned about Hand in Hand Afghanistan and, excited by the prospect of earning an income, joined the programme to learn the basics of poultry farming.

Over five days, Mahgul learned not only how to properly raise and care for chickens, but also how to run and develop a business and manage her finances. At the end of her training, she received her own chickens, as well as feed and a number of tools, as part of an enterprise start-up kit designed to help her succeed.

Forging a future

Not even a year into her new endeavour, Mahgul’s farm has grown to include 32 chickens that produce an average of 20 eggs each day. Though some are kept to help feed her family, she sells most of them, earning a monthly income of nearly 3,000 AFN (US $40).

That income has not only helped her support her family, but it has also allowed her to help put her children through school.

Less than a decade ago, Mahgul was left helpless as she and her family were forcibly deported from her home. Now, she has not only been empowered to forge her own future, but she has cultivated one for her children as well.

Mahgul’s results

Settled after forced relocation to Afghanistan

Increased monthly income from 0 to 3,000 AFN (US $40)

Able to contribute to school fees for her children

‘This good life makes me feel happiness’: Kipkoech, shop owner

Kipkoech Bernard Cheruiyot was having a hard time supporting his family as a farmer. An unpredictable climate in Kenya’s Bomet County meant frequent droughts often affected his yield, making it hard to earn a profit that would support his wife and three children.

After learning the basics of shopkeeping from Hand in Hand, though, Kipkoech, 31, has found the financial freedom he had long desired — and now has his sights set on becoming a wholesaler.

“Before, when I was only doing farming, I did not see much profits,” Kipkoech said. “When I started this business, I see how much my life has changed.”

Bomet County, Kenya

Competing for success

Poverty in Bomet County is rife: 42.9 percent of households have a combined income of less than US $3.20 a day, according to the Kenya Red Cross Society.

Agriculture is the primary means of employment in Kenya, a trend that’s particularly emphasised in Bomet, where government statistics show there are 58,000 registered farmers, primarily in tea and coffee. That competition, combined with unsteady conditions, can create plenty of volatility in the market — and financial uncertainty among the general population.

Fundamentals for success

Kipkoech, whose wife Winny does not work, was worried his family would go hungry when he learned about Hand in Hand’s Self-Help Groups, generously supported by the IKEA Foundation

Keen to expand his economic horizons, Kipkoech joined the group and learned the fundamentals of entrepreneurship, from how to start a business to the ways to make it successful.

Using the group’s Merry-Go-Round table banking initiative, he secured a loan of KES 10,000 (US $100) in November in order to set up a shop in the Kipsarwet Shopping Center, where he sells sugar, baking flour, soap, tea leaves, cooking oils, rice, maize flour and bread.

Although he acknowledged the early morning hours can be difficult, he believes they are the reason why the shop has been a success.

“I start every morning around 6 a.m.,” Kipkeoch said. “At that time, there are many customers — mostly students who like to buy pens, books, snacks. Waking up early, I can get to know them and help them before my neighbours start to open two hours later.”

Regular customers continue to arrive in the late morning hours, often buying bread, sugar and tea leaves. Kipkoech then closes the shop for the day around 4 p.m., allowing him to relax at home and go running, and it remains closed on the weekends, when he focuses on running his onion farm.

A whole new future

Whereas profit was hard to obtain as a farmer, Kipkoech has realised how much running the shop has changed his life.

“When I started to keep records, I started to see the difference,” he said. “In a day I could make KES 1200 (US $12), or maybe even as much as KES 1500. I know how much I make.”

Not only does he expect to have the original loan repaid by the time it comes due in November, he has been able to change his family’s lives as well. Already, he has built a new three-room house and bought new furniture, and he has been able to afford the fees to move his daughter, 10, into private schooling so that she may better achieve her goal of becoming a doctor.

His ambition doesn’t end there. Within the next three years, Kipkoech would like to expand his business and become a wholesaler. He believes the principles he learned from Hand in Hand have prepared him to apply for a government loan that would help make that happen.

At that point, he believes he’ll be able to make KES 10,000 (US $100) a day — a fortune vastly different from that of a year ago.

“When I look back, a lot has changed,” Kipkoech said. “I have changed my home and improved my children’s education. This good life makes me feel happiness.”

Kipkoech’s results

Learned fundamentals of shopkeeping

Guaranteed a steady income for family

Built new three-room home

Meet Frozan, who has created a buzz around Marmul

Frozan, 18, lives in north Afghanistan, a corner of the world where opportunity is scarce. Still, that never stopped her from dreaming. “We are a big family and my father, a farmer, was the only one earning – it was never enough. I have always wanted to do something to help but I didn’t know how.”

Didn’t, that is, until she met Hand in Hand. Frozan joined a Self-Help Group and quickly became a star pupil. Training led to a business plan, which led to a loan from fellow group members. Finally, she was ready: the newest and youngest beekeeper in her village. Her business has not only helped put her through school, but it has done the same for her younger siblings and even helped her parents provide for the family.

Mazar-i-Sharif, Balkh Province, Afghanistan

Keeping busy

As a student, Frozan had already achieved more than her peers, but a desire to help her family would not let her stop there.

After joining the Shogufa SHG, Frozan attended regular meetings and supplemented her schoolwork with training on microfinance, bookkeeping and business development.

“I was keen to have a business from the first group meeting until I completed [business development] training, when I understood how to run a business and what I should consider before starting a business,” Frozan said. “Therefore, with the help of my trainer, I developed a business plan.”

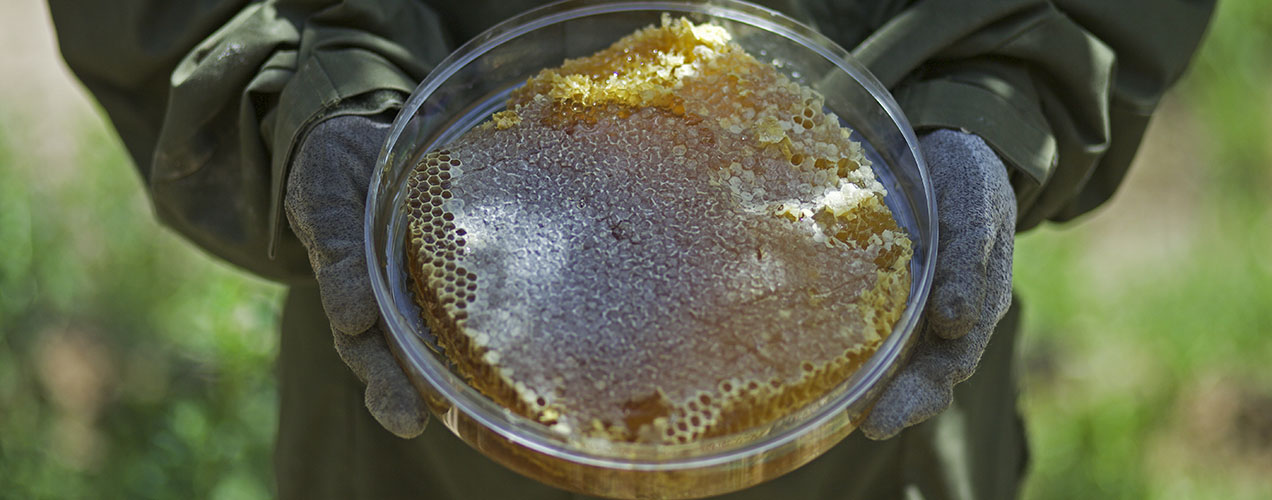

Frozan carried out a study of the Marmul district in the Balkh province in northern Afghanistan and learnt that there was a high demand for honey. After further research, she discovered that beekeeping doesn’t require much labour – a perfect arrangement for a full-time student – and so she applied for and obtained a microloan of 10,000 afghanis (US $140) so that she could purchase two boxes of bees.

Sweet success

As the youngest person in Marmul to keep bees, the SHG taught Frozan the skills she needed to look after them, as well as how to extract the honey and improve its quality and volume.

After her first year, she had harvested 16 kg (35 lbs) of honey, making enough to not only repay the microloan but to leave her with a small profit. She invested that back into her business by buying more bees, and last year, she earned 120,000 afghanis ($1,728) from the 120 kg (265 lbs) of honey produced by a collection of what had grown to 20 beehives.

“After first year of my business, I was amazed to see the results,” Frozan said. “I repaid the loan and expanded my business. Now I am paying school expenses of my two younger siblings, helping my dad in home expenses and I have my own savings for emergencies.”

Frozan’s classmates have told her they have been inspired by her business and that they would like to set up their own.

“People having a business like me can help their families to overcome financial challenges, save for emergencies and take active part in developing economy of their communities,” she said.

“Now I have learnt how to manage my activities and time, and work confidently in order to improve our lives. I am also saving for expanding my business, which will in turn generate more income for me in the future.”

Frozan’s results

Increased monthly income from 0 to 10,000 AFN (US $144)

Able to contribute to school fees for her siblings

Inspired classmates to create their own businesses

Meet Cecily, whose vertical farm has taken flight

Fifteen square meters isn’t just the size of Cecily Wawira’s rented smallholder farm. For years, it was the boundary imposed on her ambitions. But after learning an innovative growing technique called ‘vertical farming’ from a Hand in Hand Self-Help Group – along with the basics of entrepreneurship – things are looking, well, up.

“Many people here are down economically,” says the 44-year-old grandmother from Embu County, Kenya. “If they can be empowered and lifted up the same way we have, they too can become active and do things the way we are doing them now.”

Embu County, Kenya

Making ends meet

Life is changing rapidly in urbanising Embu County, home to more than 500,000 people. According to the Kenya National Bureau of Statistics, 28.2 percent of residents live below the poverty line, which the World Bank classifies as earning less than US $1.90 a day.

For those still working as smallholder farmers, life can especially hard. Problems affecting farming in this arid region range from an unpredictable climate and scarcity of water to, for thousands like Cecily, a simple lack of land.

Maximising growth

For much of her life, Cecily was a casual labourer who struggled to make enough money to purchase even basic necessities.

She rarely made more than KES 250 (US $2.50), which made it difficult for her and her husband to provide not only for themselves, but also for their two children.

“If I wanted to eat an egg or vegetables or meat, I went asking for a loan in the shop,” Cecily said.

Her fortunes changed early last year, when she learned about the Mathayo Women Self-Help Group.

With generous support from the IKEA Foundation, Hand in Hand trainers led regular morning meetings in which the women were taught the fundamentals of running their own business.

“I listened to them and I heard they had good things to say, such as the importance of having savings to improve my life and how I will benefit,” Cecily said.

That rekindled her interest in farming, but because of a lack of land, she had to be creative. With the support of the Self-Help Group, Cecily learned how to set up a vertical farm – a series of outdoor shelves holding bags of soil where vegetables grow – to maximise her limited space.

“Because here land is small, I see it’s important to plant that way,” Cecily said. “Now I benefit by eating the vegetables – spinach, kale and amaranth – and there are others I sell.”

Spreading her wings

IKEA Foundation projects Embu run by Hand in Hand East Africa.

Cecily’s calculations were correct. She was soon able to sell her vegetables, keeping some of the profit as an income and reinvesting the rest. She then began retailing bananas, which she sold for a weekly profit of KES 2,000 (US $20).

Within time, the profits from the vegetable farm and the bananas helped her dream grow bigger. Now, Cecily raises chickens and sells eggs for KES 25 (US $0.25) each. She even uses the manure as a fertiliser for the soil in which she grows the vegetables.

“The biggest difference is that I am very busy doing a lot of things and I am making good money,” she said.

Each day, Cecily aims to put aside a portion of her profit for her savings. She has been able to help her children, aged 24 and 22 with children of their own, to support their families. She has also noticed her neighbours have set up their own vertical farms.

And, with the money she has earned from her growing business, she and her husband have a new financial goal.

“Eventually I want to build my own house so I can improve my life,” Cecily said.

Cecily’s results

Set up her own farming business

Reinvested profits in order to expand

Set goal to one day own home and land

Meet Wilter, the tailor with a growing market share

Before joining a Hand in Hand Self-Help Group in Bomet County, Kenya, Wilter and her family of three could barely afford breakfast. “We ate leftover ugali [a traditional dish made of maize flour] every morning,” she says. “Now we get fresh eggs and tea.”

The 28-year-old’s tailoring business has doubled in size since she received business training from Hand in Hand with generous support from the IKEA Foundation, and today nets a profit of 8,000 KES (US $80) a month. At the same time, Wilter’s growing trainee workforce has pushed her products into new towns and villages.

Life in Bomet

IKEA Foundation projects in Bomet County, Kenya, run by Hand in Hand Eastern Africa.

Opportunities in Bomet, one of the most densely populated areas in western Kenya, are overwhelmingly limited to agriculture. The area is known for its tea and dairy industry, and most women tend to the home and cattle. Sixty percent of the working population sell crops for a living. Five percent hold permanent jobs, almost none of them women.

“Women don’t venture into business because they don’t know they can,” says Wilter. “Because of the culture, women spend a lot of time alone or at home.”

It wasn’t just an upgrade in business skills that put Wilter on the path to success, then, but a change in outlook.

A lesson in market share

IKEA Foundation projects in Bomet County, Kenya, run by Hand in Hand Eastern Africa.

Wilter got started repairing torn shirts and dresses for friends and family. After getting access to a loan via Hand in Hand, she bought some fabric and started selling her own creations. But it wasn’t until her Hand in Hand trainer taught her about market-building that she landed a contract making uniforms for her 8-year-old daughter’s primary school and things really took off. “Not only do they buy the uniforms, but they also come independently if they need more pieces as well,” she says.

“Before Hand in Hand training, I didn’t have money to do this kind of work. Now I have machines and materials,” she says. But she has no plans to stop there. With her new income, Wilter is focused on increasing her stock and enhancing her business. “My goal is to make it bigger and teach more trainees,” she says.