Meet Bernhard, the entrepreneur with a micro-business empire

Two years ago, Bernhard was running a small photocopying and computer skills training business out of his rented house. Today he has a studio in a home he owns, employs two family members in his sweet potato farming business and part-owns a community billiards room that funds a profitable pig farm. And he’s not stopping there.

An uncertain future

Young people in Kenya face many problems. Quality education is rare and expensive. Disease, including HIV, is highly prevalent, and cultural stigma often prevents you from seeking help. And even if you graduate with your health intact, Kenya’s youth bulge means competition for entry-level jobs is fierce beyond imagination, and youth unemployment rates are some of the highest in the world.

Based in rural Embu County, Bernhard is one of the many young people who refuses to let adversity stop him. Ambitious, hardworking and full of entrepreneurial spirit, he established a small photocopying business in 2014 and taught basic computer skills on the side. He joined Hand in Hand a year later, seeing an opportunity to grow his business, and is now a part of a Self-Help Group made up of similarly eager young people.

Embu, Kenya

Building an empire

With their training complete, the group devised a plan that would generate money quickly. Pooling their savings, they bought a pool table and rented a room for it in the local shopping centre. It now provides a total profit of KES 10,000 (US $100) a month – and also keeps teenagers out of trouble. “When they are gathered there together, they concentrate on one thing. So it’s difficult for them to start thinking about crimes,” says Bernhard.

The impressive income generated by the community pool table has allowed Bernhard his group to invest in a bigger project: a farm with 10 pigs, which they believe will yield a long-lasting and sustainable income.

‘I decided to be unique’

Yellow sweet potatoes

Bernhard has also used his training to improve his own business, saving up the coins he earns from photocopying. Eager to invest, he researched which crops were most profitable and eventually bought a crop of yellow sweet potato vines, employing his mother and sister to help plant them.

Despite their popularity, sweet potatoes are not commonly grown in the area. “Here people don’t value sweet potatoes very much because they think it’s an indigenous plant, so they see it as a common thing. They think they are planted by old people, rather than farmers outside Embu County,” he says. “I decided to be unique.” Bernhard capitalised on a gap in the market, and is now reaping the rewards of his ingenuity.

“Before Hand in Hand – let me be frank – I was not very successful,” he continues. “After selling my sweet potatoes, I have managed to buy a picture printer that costs 24,000 KES (US $240), and I introduced a studio inside my room.”

Between his sweet potatoes and the income generated by his technology business, he has been able to build his own home and provide for himself and his new wife.

And his next big purchase? “A sofa set for the house.”

Bernhard’s results

Owns or part-owns 4 businesses

Employs 2 family members

Bought house

Meet Zubaida, the ‘famous’ tailor from Marmul district

Four years ago, Zubaida had no job and no income. Today, she’s something of a local celebrity, “famous” for running her own tailoring business. With her newfound income, the 32-year-old is feeding her children a more nutritional diet. And with her growing reputation, she’s training six people in her community to work as tailors, just like her.

The Gul Lala Self-Help Group

Employment in Afghanistan is hard to come by. Poverty is not. Some 39 percent of Afghans live on less than US $1.90 a day, the World Bank’s threshold for ‘extreme poverty’.

Zubaida used to be one of them. Back in 2014, she was struggling to feed her five children with her family’s monthly income of AFN 7,000 (US $100). So when Hand in Hand Afghanistan offered her the chance to learn business skills as part of a Self-Help Group, she leapt at the chance.

Hand in Hand’s budding entrepreneurs are offered the chance to learn basic business skills, form a community and build a pool of savings that can be used to take their initiatives further. Zubaida joined the Gul Lala Self-Help Group and did exactly that, taking an initial loan of AFN 10,000 (US $200) to establish her own tailoring business after gaining the training and confidence she needed.

Entrepreneurial pursuits

Zubaida serves her daughter lunch

Today, Zubaida designs, makes and sells women’s clothes for AFN 200 to 450 (US $3 to $7) an item, while the clothes she makes for children fetch AFN 150 to 200 (US $2 to $3). Between them, she earns about AFN 6,000 (US $85) a month.

But the impact of her new enterprise isn’t only financial. “Now I’m able to make decisions about my kids and describe my views and opinions in a better way with my family members,” she says.

And her sense of empowerment doesn’t stop there. “My neighbours and relatives see me as a businessperson and as an instructor, which makes me proud,” says Zubaida. “My enterprise has made me famous and it has given me the courage to take part in social activities.”

Having paid her loan back to the group, she is now training six people like her in tailoring entrepreneurship. Not only has her business allowed her to build financial freedom and confidence, it has given her a platform to train and inspire others to improve their own lives.

Zubaida’s results

Monthly income: AFN 6,000 (US $100)

Training six members of her community

Feeding her five children healthier meals

Meet Saboor, the young father who saved his family’s fortunes

Walk a mile in Saboor’s shoes and you’ll know his struggle.

No, really.

Fed up with being chronically underemployed – “It’s hard to find employers who pay regular wages,” he explains – the 28-year-old husband and father had dreams of launching his own shoe business, but for years, they remained just that. When the growling in his 4- and 2-year-old’s stomachs became too loud to bear, Saboor resolved to move his family out of Afghanistan. Anywhere, he remembers thinking, would be better than this.

Then he caught wind of an NGO that was training local people to run their own businesses and, suddenly, home didn’t seem so bad.

Mazar-i-Sharif, Balkh Province, Afghanistan

Afghanistan’s quiet crisis

Imagine if during the 2015-’16 migrant crisis some 50 million people, not 3 million, arrived on Europe’s shores, hungry and desperate for work. Now imagine if Europe was one of the poorest places on Earth, lacking even the most basic services required to keep up.

That, proportionately, is the problem facing Afghanistan, the world’s largest source of refugees for more than three decades. Today, Asia’s poorest country faces the inverse problem: the world’s largest returnee crisis, with some 2.5 million people expected back in the country this year and next, chased across the Pakistan border by new visa requirements, increased police raids and deportations, and a lack of employment opportunities, according to the UN.

Afghanistan’s returning millions need access to housing, education, clean water and healthy food. In short, they need jobs. In some cases, Hand in Hand is working directly with this growing cohort, particularly around the country’s growing poultry value chain. But the scale of the crisis means all of our programmes have taken on new importance.

Where will returnees get jobs if not from employers?

A shoe-in for success

Saboor

Materials, margins, marketing – Saboor learned a lot from his Hand in Hand trainer. “I am so thankful for the support and guidance,” he says. Today, his Noman Subhan brand shoes and sandals are all the rage in the markets and stalls of Mazar-i-Sharif, Afghanistan’s second-biggest city.

Quality, of course, will cost you – precisely AFN 625 (US $9) a pair. Multiply Saboor’s mark-up of AFN 135 (US $2) per pair by roughly 145 pairs a month and the Phil Knight of Mazar-i-Sharif is making 19,575 AFN (US $285) a month in pure profit. It’s enough to make sure his children are well-fed, sheltered and educated. Enough to make his wife proud. Enough to fuel realistic ambitions of international sales in neighbouring Uzbekistan. And enough employ six of his neighbours.

All of them, he adds, earn a regular wage.

Saboor’s results

Average monthly business income: 19,575 AFN (US $285)

Number of employees: 6

Better health and education for his children

Value chains: all the buzz

Pauline Chemboi hated bees. They buzzed in your ear. They dined openly on your fruit. And the more you gave them a respectful distance, the more they refused to leave you alone. That was in 2013, back when she would sit up at night and worry about the next day’s meal. Today, she loves bees. And she’s never slept, or eaten, better.

“Owning beehives is traditionally a man’s job; we didn’t know we could it,” explains Pauline, beaming, as three of her Baringo County Self-Help Group colleagues tend to the hives behind her. “Many of us were afraid to start the venture, yet now here we are.”

Right around now is when most Hand in Hand Entrepreneur Stories would turn to our training or the generosity of our donors – and to be sure, both played a role. But this is a different kind of story, one that sheds light on the final, most opaque step in Hand in Hand’s job creation model: ‘linking members to larger markets’. Unique among third sector case studies, it starts not with indomitable women of X or the poverty-beating ambitions of Y, but with Ernesto Simeone, a gregarious Italian who saw an ad in the newspaper and decided he could make an easy buck.

Creating jobs in four (not so) simple steps

Hand in Hand’s four-step model is straightforward enough. First, we mobilise Self-Help Groups who support each other, save together and learn together. Second, we teach them the basics of business: bookkeeping, marketing and, if they lack bankable skills, the ins and outs of high-margin vocations such as honey production. Third, we provide microcredit to help them get up and running. And fourth – well, here’s where things can get a bit tricky.

At its core, ‘linking members to larger markets’ means helping them reach more customers. Sometimes that’s as simple as helping improve their branding and packaging. Other times, it means getting their products into actual, physical markets in nearby towns. Increasingly, however, we’re dreaming bigger and plugging our members into regional, national and even international value chains. It’s a strategy borne of a simple need: to make sure members’ businesses long outlast our support.

Which brings us to Ernesto.

The Italian job provider

Ernesto Simeone

Ernesto Simeone is a fitting poster-child for international value chains. Italian by heritage, he was born in Kenya, the son of an Italian POW who’d been “frogmarched from Ethiopia by the Brits”. His career in honey stretches back to 1994, when a Japanese company placed an advert in a Nairobi newspaper. “They were looking to buy honey from East Africa. I thought, that’ll be easy: buy some honey from the small-scale guys and sell it,” he says. “It didn’t work out that way.”

For one, the local ‘industry’, if you could call it that, needed modernising. “For me, the honey industry in east Africa is not beekeeping; it’s honey hunting. The quality being produced by these small-scale farmers is not very good. In fact, you can’t trade with it on the international market,” says Ernesto, whose company, an SME called African Beekeepers Limited (ABL), employs about 10 Kenyan staff. Local producers were sceptical of his outsider’s methods. And even if they hadn’t been, Ernesto lacked the infrastructure to train them at significant scale.

If only I could partner with an NGO that had proven experience training grassroots entrepreneurs, he thought.

Great minds

Two-hundred miles south in Nairobi, Hand in Hand Eastern Africa staff were poring through data on value chains. “If only Hand in Hand could partner with a honey producer capable of providing a market for our members,” someone said.

With so few players in Kenya’s honey industry, it wasn’t long before Hand in Hand rang ABL. Days later, they were in a room with Ernesto devising a sustainable, profit-based model that would benefit him, Hand in Hand and, most importantly, our members.

Here’s how it works.

Hand in Hand teaches Self-Help Groups the skills they need to run successful beekeeping enterprises, technical and otherwise. It also provides them with the means: microloans to pay for inputs such as beehives and suits. Ernesto’s company, ABL, sells them those inputs. It also provides them with an ongoing, reliable market – purchasing, packaging and selling their honey under its Bizzy Bee brand.

“Last week, our harvest was 188 kilos,” says Ernesto. “I paid Hand in Hand’s members 70,000 KES (US $700) direct through mobile banking. It’ll retail for about double that at supermarkets.”

As their profits grow, members repay Hand in Hand’s loans – which, in turn, get cycled back to new members. And for as long as people eat honey – whether in Japan or at home in Kenya – producers like Pascaline have work.

“This project has helped us a lot,” she says. “We can pay school fees and food for our homes. Every woman can now support her family.”

Results

1,400 entrepreneurs in honey value chains countrywide

Average yield per co-operative: 70,000 KES (US $700)

Women’s participation rate: 80%

Meet Mageswari, the toy shop owner bringing joy to Pondicherry’s children

By Shivani Kochhar

Mageswari, a toymaker’s daughter, had always dreamed about owning a toy shop. But with no secondary school education and few assets to her name, her dream was destined to never become reality.

That’s life in India, where two out of three working households earn less than 1,000 INR (US $15) per month. Mageswari’s was one of them. She also had a son to worry about.

It runs in the family

Inspiration struck Mageswari’s brother: they could team up to open a toy shop together and sell their father’s hand-carved wooden toys. After all, in business two heads are better than one. But Mageswari’s brother also lacked a credit history or assets, and even microfinance lenders would not consider giving them a loan.

Pondicherry, India

A helping hand

That’s when Mageswari heard about Hand in Hand. The 40-year-old joined a Self-Help Group five years ago with the intention of securing a loan to bring their business idea to fruition. After completing her training, she pooled what little savings she had with a microloan from Hand in Hand India, bought the necessary equipment and rented a shop in the centre of Pondicherry.

The dream team

The toyshop was a huge success, reaching a monthly turnover of 57,000 INR (US $880). Brother and sister employ four of fellow Self-Help Group members, spreading their success around the community. “Other toy shops in Pondicherry only sell plastic toys – they are cheaper than our wooden toys but they also last less long,” says the soft-spoken but self-assured Mageswari. These toys leave a legacy.

The toyshop was a huge success, reaching a monthly turnover of 57,000 INR (US $880). Brother and sister employ four of fellow Self-Help Group members, spreading their success around the community. “Other toy shops in Pondicherry only sell plastic toys – they are cheaper than our wooden toys but they also last less long,” says the soft-spoken but self-assured Mageswari. These toys leave a legacy.

Mageswari’s brother, a born entrepreneur, took the initiative to reach out to local schools using a mail marketing campaign and the local press. The schools now place large orders for their toys. “I couldn’t have done this without Hand in Hand’s training and support,” he says. The siblings have even expanded the product range to include specialist Montessori toys.

A fairytale ending

Today, Mageswari has a degree of financial independence she could never have dreamt of before, along with a television and refrigerator to prove it. Most importantly, she can pay for her son’s college education. Before the toy shop, annual fees of 75,000 INR (US$1,166) made college unthinkable. Today, her son is in his second year of electrical engineering.

“We plan to expand our business by buying our own premises and additional machinery,” says Mageswari. Watch this space: maybe one day this brother-sister act will build their own toy shop empire.

Mageswari’s results

Toy shop earns 57,000 INR (US $880) a month

Able to put her son through college

Employs 4 staff from the community

Meet Manimozhi, grinding away for her family’s future

By Shivani Kochhar

With a grandchild on the way, Manimozhi needed funds fast. Her family business, a flour mill, was failing. But without capital and expertise she couldn’t change her fortunes.

A new family member

Manimozhi wanted to give her grandson the best start in life; in Pondicherry, this means being born in a private hospital. Only 1.2 percent of Indian gross domestic product is spent on public healthcare, and many government hospitals lack basic standards of hygiene, particularly in rural areas. For people like Manimozhi, they are an absolute last resort.

Pondicherry, India

Becoming a businesswoman

Manimozhi joined a Hand in Hand Self-Help Group with the hopes of using her loan to pay for the costs of the birth. Instead, after receiving training in financial literacy, she ploughed the loan into the faltering mill business she’d inherited from her father and paid for the birth using pure profit.

Manimozhi joined a Hand in Hand Self-Help Group with the hopes of using her loan to pay for the costs of the birth. Instead, after receiving training in financial literacy, she ploughed the loan into the faltering mill business she’d inherited from her father and paid for the birth using pure profit.

Manimozhi’s mill grinds rice, wheat and grains into flour or oil. It’s bring your own grain: customers are only charged for the grinding service. Using her loan, Manimozhi modernised the mill with an automated elevator that feeds paddy into the mill more quickly, speeding up production. Now, customers travel for 30 minutes by tractor to come to the mill. “I’ve opened my own private bank account so I can save better,” she says.

Keep calm and carry on

Those savings came in handy when the mill was damaged, its roof torn clean off, during a severe statewide storm that killed almost 50 people in Pondicherry and nearby Tamil Nadu. The cost of rebuilding was IRN 50,000 INR (US$ 766). With her savings in store, Manimozhi wasn’t held back: she got on with the rebuild quietly.

Manimozhi’s is now the longest standing flour mill in the area. The business has been in the family for 55 years and is already providing for two more generations. She now knows how to support her family through the good times and the bad.

Manimozhi’s results

Employs 4 staff members

Pays for grandchildren’s education

Supports 3 generations of her family

Meet Komala, who’s bringing beauty back into business

By Shivani Kochhar

Running her own beauty salon had been a dream of Komala’s since childhood, but lacking education and in her mid-30s, she was a housewife living on the brink of poverty instead.

The ugly truth

In India, one in five people are considered ‘poor’, living on less than $1.90 a day. This is partly due to the nature of employment: only 17 percent of jobs are salaried and one-third are irregular. Women looking for work have even more hurdles to overcome as there is large gender gap in the workforce. Just 27 percent of women participate in the labour force at all, compared to 79.1 percent of men. Clearly, the odds were against Komala – so she decided to take matters into her own hands.

Transformation

Things changed for Komala when Hand in Hand arrived in her panchayat. Inspired by her Self-Help Group’s promise of beautician training, not to mention a loan to get her started, she soon finished her training and opened up shop. With four beauty salons nearby already, she established a competitive advantage based on comparatively low prices and superior customer service. She is especially busy during wedding season when everyone needs to be pampered to perfection.

“Some of my neighbours have been motivated to start up a business of their own,” she says.

A touch of sparkle

Even with business humming, Komala found she had downtime during the day. That’s when she established a side-business embellishing saris with sequins and embroidery that now accounts for 30 percent of her income. But she wasn’t done there. Sensing opportunity, Komala qualified to become a beauty trainer herself, and today teaches up to 20 students a month. She earns INR 1,000 (US $15) per student and gets the satisfaction of helping other women start their careers. “Even though I am training members of my community, they see me as a professional,” says Komala.

Pondicherry, India

Looking forward

Together, her three streams of income bring in an average of INR 51,600 (US $770) a month. That’s enough to pay for life-changing appliances including a refrigerator and air conditioner. She can also afford some luxuries such as a TV. Next up: Komala is saving to buy a permanent home for her family and, when they grow up, pay for her two children’s university. “I hope that my son will become a doctor,” she says.

And her plans for her business? “I want to brand my salon with my own name, to make it stand out from others in the neighbourhood.” Sounds like a winning idea to us.

Komala’s results

![]()

Earns INR 51,600 (US $770) a month

![]()

Able to give her children a university education

![]()

Helps the community by teaching her skills to budding beauticians

Meet Jagadeeswari, the spice-seller with SME status

By Shivani Kochhar

Jagadeeswari could give any entrepreneur a run for their money. Five years ago, she was distributing her spices as free samples to neighbours and her business was making a loss. Fast-forward to today and she has won a state prize for ‘First-Generation SME Entrepreneur of the Year’. Her distribution network spans 200 shops across her home state of Tamil Nadu, and she sends her spices as far away as Malaysia. It’s a homegrown business gone global, and an unlikely success story in a state where 22.5 percent of people live below the poverty line, earning less than US $1.90 a day. Jagadeeswari’s successes are an exception to the rule rather than the norm – something that Hand in Hand aims to change.

Pondicherry, India

The perfect blend

Jagadeeswari flourished at her Hand in Hand Self-Help Group. The energetic 46-year-old is a natural leader, and her fellow group members quickly selected her to be in charge. Jagadeeswari started selling her spices at food fairs and managed to grow her client base district-by-district until she had established a state-wide network. Recognising her potential, Jagadeeswari’s Hand in Hand trainer provided her with special training in bookkeeping and packaging.

“Joining the Self-Help Group changed my life totally,” says Jagadeeswari, who now produces a range of around 40 all-natural spices and food products. She is the only producer in town with such a wide range of condiments.

Sugar and spice

Jagadeeswari wanted to increase her product range and hit a winner: Sarpath. A refreshing all-natural sweet soda, it’s perfect for washing down all those spices. Now she earns 35,000 INR (US$ 525) every month in pure profit. She also employs five staff including her husband, who helps with marketing and sales. He’s pleased for Jagadeeswari: “I’m very happy about my wife’s success.”

Jagadeeswari wanted to increase her product range and hit a winner: Sarpath. A refreshing all-natural sweet soda, it’s perfect for washing down all those spices. Now she earns 35,000 INR (US$ 525) every month in pure profit. She also employs five staff including her husband, who helps with marketing and sales. He’s pleased for Jagadeeswari: “I’m very happy about my wife’s success.”

Woman power

As business is booming, Jagadeeswari has bought a separate building for her work and invested in a packing machine. Besides her husband, all her employees were formerly housewives and members of her Self-Help Group. Most importantly, the income generated from her spice business finances her son’s architectural training. Investing in her son’s education has already paid off – he helps her to do her marketing and created a website for the business. Jagadeeswari‘s children now call her “mother role model”. She’s their inspiration.

As for her Entrepreneur of the Year award, Jagadeeswari says she’s happy for the publicity – as long as it attracts new clients. Clearly, she never stops being the businesswoman.

Jagadeeswari’s results

Earns 35,000 INR (US$ 525) net profit per month

Sends her son to architectural school

Achieved SME level status

Meet Savitah from Kanchipuram, who’s gone from paper dreams to paper plates

By Shivani Kochhar

Savitah’s paper-plate business was making no profit at all. The 26-year-old newlywed had little experience of business. But she did have a drive to succeed.

A woman on a mission

Savitah was inspired by her friends in Bangalore to go into business. Most of all, she admired the bravery of these female entrepreneurs for breaking the status quo: just 27 percent of women participate in the labour force at all, compared to 79 percent of men. Savitah initially attended a Self-Help Group to finance a paper-plate-making machine. One thing led to another: she completed bookkeeping training and realised that 85 percent of her total costs went on raw materials, preventing her from making a profit.

Savitah put every effort into sourcing cheap materials, knowing they could make or break her business, searching as far afield as Delhi (2,200 km away). In the end, she managed to find a supplier much closer to home in Chennai.

The secret to success

Today Savitah consistently undercuts her competitors – and watches her sales soar. With her savvy sourcing, she maintains a healthy 27 percent profit margin. This is boosted by the sale of off-cuts to paper merchants who use them to make recycled paper. It’s business-smart and environmentally sustainable. Her monthly net income, once zero, is now 21,500 rupees (US $350).

Kanchipuram, Tamil Nadu

Independent woman

Most of Savitah’s income has been reinvested in the business, but she keeps a little for herself so she can feel more independent in her daily life. “When I leave the house now, I don’t need to ask my husband for money,” she says.

Her husband questioned the need to buy a second machine but Savitah’s reasoning was as simple as it was compelling: “Anyone who buys a paper bowl will also need a paper plate, so let’s buy that machine, too.” Although she’s an entrepreneur at heart, Savitah says, “Before joining the Hand in Hand group, I would not have been confident to make a decision like that on my own.”

Team leader

Savitah exudes a quiet confidence and determination, and since she first joined the group she’s persuaded five new members to join. Her peers chose her as their group leader, a role that entails managing meetings, teaching basic business skills and encouraging members to start their own businesses. A fast learner herself, she observes: “Sometimes it takes members so long to get up to speed with the concept; you have to be patient until they understand the approach.”

A working mum

Now 31, Savitah is expecting her first child but is confident that she will continue on her path as an entrepreneur and group leader. “I enjoy being independent and helping others to be independent, too,” she says.

Savitah’s results

Earns 21,500INR (US$ 350) net income per month

Voted to be the leader of her Self-Help group

Has financial independence

Meet Aloys, the barber from Muruma

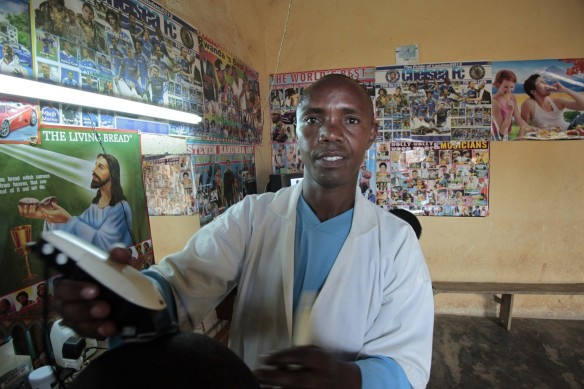

Aloys Nsabimana fires up his electric clippers and gets to work. Overhead, Chelsea FC’s 2013 line-up and a group of “new super stars” look down from a jumble of posters. A customer watches TV.

Squint hard enough and you’re almost in London. But this is Muruma village, Bugesera District, Eastern Province, Rwanda – in short, a world away – where the floors are swept clean but there’s no tile underfoot, just raw earth, and the posters conceal crumbling mud brick.

Business is buzzing

Ask Aloys how CARE and Hand in Hand have changed his life and he’ll happily count the ways. “Before I had nothing – nothing – to spend each day. Now I can spend 1,000 RWF (US $1.45) or 1,500 RWF (US $2.20) in a morning. I have a cow. I have a house. I have wife and five children. I can pay school fees, I can buy health insurance and when the children are sick, I can buy medicine.”

His secret: electricity. There are plenty of barbers in Bugesera District, but despite government plans to electrify 70 percent of homes and businesses nationwide by 2017, only one is connected to the grid. Want a buzzcut? Aloys is your man. Some TV? He’s got that covered, too. Factor in his side business charging mobile phones and the 40-year-old is making 180,000 RWF (US $260) a month – almost five times the national average.

A dark past

Aloys was 20 years old when the genocide literally decimated Rwanda, displacing an estimated 800,000 people and killing some 800,000 more. The country has come a long way in the 20 years since: in 2014, the UNDP noted Rwanda’s “accelerated progress” on 15 MDG indicators – the fourth most anywhere – and in 2017, the World Bank’s “ease of doing business” index ranked it 56th to Belgium’s 42 and Luxembourg’s 59. But there’s still a long way to go. Globally, Rwanda ranks 158 of 189 on the UN Human Development Index – and it gets worse. In rural Rwanda, home to Aloys and the rest of Hand in Hand’s entrepreneurs, poverty is three times greater than in the city.

The country’s dual fortunes – improving, but not fast enough – are neatly summed up in its education rates. Primary school enrolment is now above 98 percent, the highest in all of Africa. But more than three-quarters of students, 72 percent, don’t make it to secondary school.

A bright future

Aloys was one of them. Lacking education – though not the entrepreneurial spirit – he started off selling clothes in Kigali, then moved to the country to start his own farm when the venture failed to take off. When that failed too, he set up shop underneath a tree in Murama village, Ngeruka sector, and started cutting hair at 100RFW a pop. Finally, he’d found his calling.

But it wasn’t until 2009, when he joined a local Village Savings and Loan Group organised by Hand in Hand field partner CARE, that he also found success.

But it wasn’t until 2009, when he joined a local Village Savings and Loan Group organised by Hand in Hand field partner CARE, that he also found success.

The going was tough to begin with. In the months following the group’s inception, Aloys and others could barely scrape together 150 RWF (US $0.20) per week. Today, having all met success, they’re each saving 500 RWF (US $0.70). It was a loan for 280,000 RWF (US $400) that enabled Aloys to start his first barbershop, still going strong with help from two employees, at home. Buoyed by his initial success, and with help from a Hand in Hand business trainer, he next applied for a loan of 500,000 RWF (US $700) from the Savings and Credit Organisation.

Plans to expand

Aloys knows he won’t be the only barber in Bugesera with electricity for long. That’s why, ever the entrepreneur, he plans to take a course on cutting women’s hair just as soon as he becomes debt-free. A third loan will follow, this one to pay for the resulting equipment. He’ll probably get some new posters, too.

Aloys’ results

Possible to provide health insurance and medicine for his family

![]()

Monthly income of 180,000 RWF (US $260) – almost five times the national average

Able to send all of this children to school

Hand in Hand Eastern Africa and CARE Rwanda are co-operating to empower some 100,000 Rwandans, mostly women, to work their way out of poverty by running their own sustainable businesses. The three-year, US $3.2 million partnership is grounded in our shared belief in the power of entrepreneurship to fight poverty.