95% of Hand in Hand members report improved quality of life

From designing new projects to evaluating old ones, Hand in Hand puts our members at the centre of everything we do. So last year, we asked 60 Decibels – experts in measuring impact through a “customer feedback lens” – to find out what our members in Kenya are saying about our work.

For two weeks in November, the team at 60 Decibels interviewed more than 170 members who’d completed our training, all within the last two years.

Here’s what they had to say:

- Hand in Hand’s training is useful. 95 percent of respondents were still using it in their business.

- Hand in Hand’s training improves people’s lives. 95 percent saw improvements in their quality of life after completing our training. Bigger incomes were the main reason why.

- Hand in Hand goes where other NGOs don’t. 92 percent of respondents said there was no alternative to Hand in Hand where they lived.

- Given a choice, they prefer Hand in Hand. Among respondents who had an alternative, 85 percent said Hand in Hand was better.

- They could use more credit. Asked for suggested improvement, 34 percent of respondents suggested increased financing, the most common of any response.

Conducted before the threat of coronavirus was known, the survey will nevertheless help us tailor our post-Covid-19 response, providing insight into what’s working for our members and where we can be of more help. More on that in weeks in and months to come.

Hand in Hand named ACT Charity of the Year 2018

Hand in Hand International is proud to announce our selection as the Association of Corporate Treasurers (ACT) Charity of the Year for 2018/19.

The award, which culminates at the ACT Annual Dinner in November, follows a competitive bidding process to the ACT charity committee. Proceeds will fund an entire Kenyan village’s journey from subsistence to success, creating an estimated 275 new microbusinesses and 350 new jobs.

“From financial literacy training to the creation of sustainable microenterprises, so much of Hand in Hand’s work centres on sound financial management,” said Hand in Hand International CEO Dorothea Arndt. “That’s why it’s with particular pleasure that we accept this honour from Britain’s professional body specialising in corporate treasury.”

Although the designation lasts all year, fundraising peaks on 14 November with a charity auction at the ACT Annual Dinner at the Grosvenor House Hotel in London, hosted by Sandi Toksvig of Great British Bake Off and featuring John Kay, one of Britain’s leading economists, speaking on behalf of Hand in Hand.

We are looking for volunteers to help in those efforts, attending the dinner to speak with interested ACT members about our work. For more information about how you can help, please email Hand in Hand Head of Media Ann Dickinson.

To read the ACT’s Charity of the Year announcement, click here.

How efficient is Hand in Hand, really?

Founded by one of Europe’s best business minds, Hand in Hand has long put efficiency at the core of our work. But with a job creation model few others employ, benchmarking that efficiency has often been difficult.

Now, thanks to two new World Bank studies, that’s beginning to change. Published this year, both studies consider training programmes similar to ours – one in Kenya, the other in Togo – finding significant increases in profit in both cases.

Neither finds gains on par with Hand in Hand’s.

Study one, Kenya: Zero-sum gains?

Is one businesswoman’s gain another’s loss, or does a rising tide lift all boats? That, in effect, is what the World Bank set out to discover when it monitored an International Labour Organization (ILO) business training programme in Kenya broadly similar to Hand in Hand’s. With a sample size of 3,500 micro-enterprises, the randomised experiment measured the business incomes of ILO programme members versus their non-member neighbours, concluding that ”business training can help the overall market grow.” More importantly, for the purposes of this blog, it also discovered that monthly business incomes among programme members were 15 percent higher than among business owners that had not received the training.

Study two, Togo: The psychology of entrepreneurship

A second study, published in Science and featured in The Economist, considered another angle: psychology. Here, researchers from the World Bank, the National University of Singapore and Leuphana University in Germany partnered with the Government of Togo to follow three groups of small business owners who rarely kept books and almost never wrote business plans, earning an average of US $173 a month. The first group, a control group, received no training at all. The second group received training in conventional subjects such as accounting and financial management. The third group received training based on psychological research, designed to teach soft skills such as initiative and persistence.

Those skills, it turns out, are crucial: profits rose by an average of 30 percent among members of the third group. Perhaps more interesting, however, was another finding: the conventional training group saw no uplift at all.

Study three, Rwanda: Hand in Hand

So, how does Hand in Hand stack up?

In the ILO programme in Kenya, business profit was 15 percent higher for programme participants ($86) than non-participants ($75). In the World Bank’s partnership with the Government of Togo, monthly business profit was 30% higher for those that received the psychology base training ($224) compared to those that did not ($173).

And in Hand in Hand’s partnership with CARE in Rwanda, according to an independent study – the most recent, relevant research we have – monthly business incomes were 75 percent higher for those that received the enterprise training ($48) compared to those that did not ($29).

That’s more than double the World Bank’s programme in Togo, and five times the ILO programme in Kenya.

By the numbers

ILO, Kenya: 15% higher profit for enterprise trainees

ILO, Kenya: 15% higher profit for enterprise trainees

World Bank, Togo: 30% higher profit for psychology-based training

World Bank, Togo: 30% higher profit for psychology-based training

Hand in Hand/CARE, Rwanda: 75% higher profit for enterprise trainees

Hand in Hand/CARE, Rwanda: 75% higher profit for enterprise trainees

Hand in Hand Country Manager Stephen Wambua was responsible for running our operation in Rwanda. He credits Hand in Hand’s dual-focus on hard and soft skills with the result.

“Yes, Hand in Hand teaches conventional business skills – our members would be lost without them,” says Stephen. “But our trainers’ capacity to inspire and motivate, along with mutual support among group members, is what makes our model work. It is, for lack of a better term, our ‘secret ingredient’.”

Hand in Hand will continue to seek out quality research to benchmark our programmes. And just as we always have, we’ll keep putting efficiency at the centre of our work.

Insights from Participatory Evaluation Processes: Adapting to Local Demands

This article previews Hand in Hand’s peer-learning session at the SEEP Annual Conference 2017. It first appeared on The SEEP Network blog

Your proposal was so scalable, it made USAID weep. Your logframe, so flawless it was exhibited at MoMA. Bono himself called to congratulate you on a “totally rockin’ independent baseline study”. But one year into program delivery, credit uptake is waning and dropout rates are creeping higher by the week.

What went wrong?

That’s the question new SEEP member Hand in Hand was forced to confront when two of our programs – one in Afghanistan, the other in Kenya – were threatened by similar issues. Despite more than 10 years’ experience training Savings Groups members how to launch their own microenterprises – resulting in more than 3 million new and improved jobs – we found ourselves humbled by an inescapable truth: nothing gets in the way of a masterfully designed program quite like reality. Adaptive management isn’t merely crucial to success – it’s necessary to survive.

This blog, and our session at the 2017 SEEP Annual Conference – ‘Insights from Participatory Evaluation Processes: Adapting to Local Demands’ on Tuesday, October 3 at 2:15pm – ponders a central element of adaptive management: feedback. In doing so, it posits a package of feedback mechanisms that can be (more or less) universally applied to produce useful learning, drawing on examples from the aforementioned cases, plus a third from VisionFund in Tanzania.

The learning that these mechanisms produced varied across contexts, but in each case the results were transformative, compelling Hand in Hand to redesign its theory of change and exit strategies in Afghanistan and Kenya respectively. Meanwhile in Tanzania, VisionFund applied a similar package of mechanisms during its pilot phase, and shares its experience of taking learning to scale.

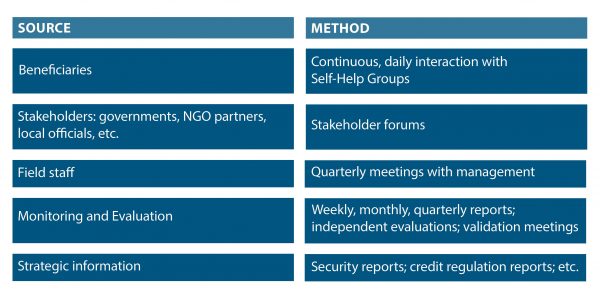

The Big Five: Feedback Mechanisms for Useful Learning

Feedback is only as good as the sources that provide it. In order to obtain the fullest picture possible, our package of mechanisms draws on the following sources and methods:

Each of the following cases employed our package of mechanisms. All have been edited for brevity. For the full picture, please attend our session on October 3.

Case One: Hand in Hand, Afghanistan

Occasionally, sources of feedback are in perfect harmony. Such was the case for Hand in Hand Afghanistan, who administered an Enterprise Incubation Fund (EIF) to finance members’ microenterprises where other institutions wouldn’t. Increasing numbers of beneficiaries said they were loath to take loans in remote rural areas where the Taliban had identified credit programs as an opportunity to disrupt NGO activity, branding them as a Western imposition. M&E data showing reduced uptake confirmed their waning interest. Other NGOs had by and large abandoned cost-recovery models in favor of flat-out grants, rendering microfinance even more unattractive. Field staff reported difficulties in recovering loans (and in some cases received anonymous threats). And strategic information pointing to a resurgent Taliban provided scant hope Afghanistan’s credit environment would improve anytime soon.

With all sources of feedback pointing in the same direction – decisively away from our microfinance component – Hand in Hand closed the EIF, adopting productive asset transfer in its place. In the time since, we have distributed some 21,300 Enterprise Startup Toolkits containing all the necessary inputs to launch a business in nine accessible, high-margin sectors such as beekeeping and tailoring, designed to maintain the self-help ethos that lay behind the credit component. Feedback has again been unanimous – this time in our favor.

Case Two: Hand in Hand, Kenya

Things would not be so straightforward in Kenya, where Hand in Hand’s EIF faced the opposite problem: it was too popular. Prior to October 2016, we provided three cycles of subsidized microcredit to members. Not surprisingly, beneficiaries were happy to continue borrowing at slightly below-market rates. But field staff complained they were overworked – tied to old members by cycle after cycle of credit while juggling ambitious recruitment targets for new members. The M&E data agreed: recruitment was indeed slowing down. Strategic information meanwhile pointed to a robust ecosystem of local MFIs, suggesting credit was available from other institutions.

Staff and management met in September, 2016 and immediately embarked on a set of program reforms, reducing the number of loan cycles from three to one. A 27-month phase-out strategy was also agreed, whereby groups would receive nine months of intensive training, 12 months for the EIF credit cycle, and six months of support on market linkages for commodities and loans. Finally, it was agreed that after 27 months, we would help mobilise members into co-operatives known as Community-Based Organisations that would help them lend to each other and gain access to bigger markets and value chains.

Initial feedback suggests the changeover is working favorably.

Case Three: VisionFund, Tanzania

From October 2016 until August 2017, VisionFund Tanzania, World Vision Tanzania and private sector grower/exporter the Great African Food Company (GAFCo) partnered to run seven pilots in different regions of Tanzania with more 3,000 smallholder sunflower and kidney bean farmers. The goal was to improve these beneficiaries’ outputs and, ultimately, their livelihoods.

Involving technology, crop insurance, loan credit processes, payment to farmers, and beneficiary engagement and education, the pilot was highly complex, and field staff reported challenges testing so many combined elements in a variety of locations. But partners had identified both a need and an opportunity: GAFCo needed to generate and test volume and quality for its European buyers, and there was an opportunity to test the approach in parallel across regions.

A major review took place in July 2017, following a review process experiment in June. Senior management from the three partners met with beneficiaries and external stakeholders, including village elders and local and regional government, as part of a 10-day M&E trip visiting each of the pilot locations and engaging in detailed conversations. The process resulted in identifying improvements in beneficiary education, explaining better to village authorities the detail behind areas such as crop insurance, and generating buy-in from local officials.

The model has now been adapted for a wider rollout from October, with an ongoing monitoring of the engagement with beneficiaries and other stakeholders to test the scalability and acceptability of the updated model and improvements in client training.

Hand in Hand creates 3 millionth job

Fourteen years ago, Percy Barnevik and Dr Kalpana Sankar joined forces to expand a small charity in southern India that provided free schooling to children working in the local silk trade. It was called Hand in Hand.

They soon realised the real problem wasn’t a lack of schools; it was the desperation that forced parents to send their children to the factories in the first place. “We had to attack the root cause of the problem: poverty,” says Barnevik.

Fast-forward to today and that’s exactly what Hand in Hand has done, fighting poverty with business and skills training from Afghanistan to Zimbabwe and in eight countries in between. Today, we’re proud to announce a major milestone in our story: the creation of Hand in Hand’s 3 millionth job.

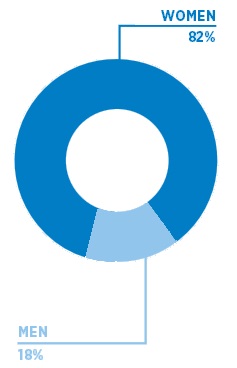

“Even when they’re undernourished, downtrodden and illiterate, Hand in Hand’s entrepreneurs have an enormous will,” says Barnevik, now Hand in Hand’s honorary chair. “When they get a chance they’re not letting it go by. These women can move mountains.”

Here’s to fourteen more years, millions more jobs and more moved mountains.

Hand in Hand speaks at World Bank

Washington, DC – The world’s poorest residents are doomed to stay that way until governments do more to nurture them as entrepreneurs. That was the message delivered by Hand in Hand Eastern Africa CEO Pauline Ngari to hundreds of MPs from dozens of countries at the World Bank last week.

Speaking to the Global Parliamentary Network, a group of policymakers who meet each year as part of the World Bank-IMF Spring Meetings, Pauline urged parliamentarians to:

- adopt accelerator programmes to help grow SMEs;

- put entrepreneurship studies front and centre in national curricula;

- foster relationships between microfinance institutions and training organisations.

Her session, ‘Fighting Inequality Through Job Creation & Growth’, also featured speakers from the World Bank, IMF and Peace Child International. It preceded a roundtable discussion featuring Christine Lagarde, Managing Director of the International Monetary Fund, and Jim Yong Kim, President of the World Bank.

“Delivering programmes is what we do – and advocacy helps us do it,” said Hand in Hand International Co-CEO Dorothea Arndt. “The World Bank is the perfect venue to share our message, establishing jobs and entrepreneurship as key planks in the development agenda. Thanks, Pauline, for sharing it so ably.”

Youth Job Creation

The conference also hosted the launch of the ‘Youth Job Creation Policy Primer – 4th Edition’, a document outlining the problem of youth unemployment and proposing solutions for policymakers. Hand in Hand figured centrally, not least for our Entrepreneurship Clubs and four-step ‘systems approach’ to job creation. Several case studies featuring our members were also featured.

Click here to visit the policy primer website.

Hand in Hand a ‘centre of excellence’, says review

Hand in Hand Eastern Africa is a “centre of excellence in training and transforming of Self-Help Groups”.

That’s according to an independent review published by the Abymas Development Practices Centre, a Zimbabwe-based evaluation agency, and funded by the Swedish International Development Cooperation Agency (Sida)/the Swedish Embassy in Nairobi.

The review comes off the back of a two-year, SEK 20 million (US $2.3 million) programme in Kenya, which concluded in March and aimed to achieve three broad objectives:

- To provide business training and marketing support to rural entrepreneurs, resulting in 14,000 jobs.

- To provide Self-Help Group members with access to microfinance.

- To promote green jobs and environmental resilience in partnership with the Government of Kenya’s Agricultural Sector Development Support Programme (ASDSP).

Here’s what it found.

Business training and enterprise development

“The effect of the project in reducing the number of people living below Ksh 3,000 (US $30) has been phenomenal,” concludes the review.

The result was achieved as members moved from subsistence farming into different agricultural value chains such as dairy, while others moved into retail, services, arts and crafts and more.

Retail and services were the two most lucrative types of enterprise, resulting in average monthly sales of Ksh 21,754 (US $217) and Ksh 19,156 (US $191) respectively.

“The Hand in Hand Eastern Africa model of enterprise development and job creation is unique”, the report concludes, “in that it creates a strong foundation for target groups to immediately use knowledge and skills gained to identify enterprise opportunities with the reach of individual entrepreneurs before even receiving external financing.”

By the numbers

67% of members were engaged farming at the outset of the project. Two years later, that number was down to 48%

67% of members were engaged farming at the outset of the project. Two years later, that number was down to 48% At the same time, the proportion of members working in retail and services rose from 7% to 23%

At the same time, the proportion of members working in retail and services rose from 7% to 23% 56% of members earned less than Ksh 3,000 (US $30) per month at the outset of the project. By the time it concluded, that number had decreased to only 15%

56% of members earned less than Ksh 3,000 (US $30) per month at the outset of the project. By the time it concluded, that number had decreased to only 15% At the same time, the proportion of members earning Ksh 10,000 (US $100) or more per month jumped from 9% to 27%

At the same time, the proportion of members earning Ksh 10,000 (US $100) or more per month jumped from 9% to 27%Gender, social inclusion and culture

Hand in Hand contributed “significantly to reducing gender inequality in the social and economic life of rural communities in all the targeted geographical areas,” says the report.

Before the project, “most women met during field work pointed out that their life was miserable and hopeless… as they were just working on isolated home activities for survival.” Today, “women have shown confidence in every possible sector,” resulting in “great household resilience, which changes the employment and income dynamics within the household within a very short time.”

Men’s attitudes also changed, “becoming more supportive of women’s participation in SHG activities and viewing women as equal partners in the decision-making process.”

Environmental resilience and green business

Members were “instrumental in championing key environmental initiatives within their households and communities” despite facing “several challenges”, said the report.

Barriers to success included entrenched attitudes and the cost of environmentally friendly technologies. But initiatives including “tree nurseries… stoves for energy saving, waste recycled products in peri-urban areas, water management and conservation, improved sanitation and use of organic manure” proved popular nonetheless, helping members build resilient, sustainable enterprises.

More intensive training and deeper linkages with similar projects were recommended to improve the programme.

Access to microfinance

Hundreds of members borrowed microloans from Hand in Hand Eastern Africa’s Enterprise Incubation Fund (EIF) to help grow their businesses. So far, so good.

At the end of the lending cycle, however, relatively few showed interest in climbing the finance ladder to receive higher interest loans from bigger, more formal lenders – one of the fund’s chief goals. That could spell trouble when the project concludes.

The report suggests two possible solutions.

- Work more closely with microfinance institutions and government agencies to ease members’ climb up the microfinance ladder.

- Provide two distinct types of loans: one for start-ups, another for businesses able to demonstrate market-driven growth. “This will ensure those entrepreneurs that are not growing are churned out at a pre-determined exit point within the loan cycle. At that point they will have acquired entrepreneurship skills, knowledge and experience and will have developed strong mutual support systems (internal savings) that can propel them into the future,” says the report.

Percy Barnevik on The Social Enterprise Podcast

Hand in Hand Co-founder and Honorary Chair Percy Barnevik appeared recently on The Social Enterprise Podcast, presented by Rupert Scofield, president of Microfinancial Institution FINCA and author of ‘The Social Entrepreneur’s Handbook’.

Here’s a description from the Social Enterprise Podcast website:

“On this special episode of the Social Enterprise Podcast, Rupert is joined by businessman and philanthropist Percy Barnevik. After a successful career in business – chairing companies including ABB, Sandvik, Skanska, Investor AB, and AstraZeneca – Percy founded non-profit organisation Hand in Hand International, inspired to help street children in India. Having worked in 14 countries, the organisation provides grassroots entrepreneurs in some of the poorest places in the world with the skills to start their own businesses. Percy reveals his motivations, some of the challenges, and how business informed his approach to charity.”

Listen to the podcast hereHand in Hand teams up with the IKEA Foundation on youth, climate change

Hand in Hand and the IKEA Foundation are teaming up to help thousands of women and young people in rural Kenya work towards a brighter, more environmentally friendly future.

Launched in April with a US $3.6 million grant from the IKEA Foundation, the project will help 43,200 impoverished mothers and young people in Kenya thrive as eco-entrepreneurs, even while inspiring 4,800 future business leaders at Entrepreneurship Clubs in schools. For thousands of children, the results will be transformative: full stomachs, inquiring minds and a world full of potential.

The grant is among the IKEA Foundation’s first after it announced last year it would dedicate €1 billion (US $1.14 billion) to fighting climate change.

“We believe children have better futures when their families earn sustainable incomes, which is why we are supporting Hand in Hand with a US $3.6 million grant,” said Jonathan Spampinato, Head of Communications at IKEA Foundation. “Our partnership with Hand in Hand will help thousands of women and young people in Kenya create jobs and small businesses that can stand up to climate change. We are really excited to launch this partnership and begin our work together!”

Standing up to climate change

Look at poverty differently and you’ll see entrepreneurs, full of energy and ideas. Hand in Hand’s helps harness their potential. They find a way up and out of poverty, boosted by our comprehensive job creation model.

Savings groups and business training in areas such as bookkeeping and marketing aren’t rare. Nor, for that matter, is microfinance. But where other organisations focus on one or two of these elements, Hand in Hand combines all three – then adds a fourth by connecting entrepreneurs to larger markets and value chains.

Our partnership with the IKEA Foundation goes one step further, adding another crucial element: resilience to climate change. That means creating thousands of self-sustaining green businesses in areas like water purification, charcoal briquette production and upcycling. It also means training thousands more agricultural entrepreneurs to farm organically, and to use techniques including crop diversification, irrigation, planting trees to reduce soil erosion and more.

“Impoverished rural communities are on the front lines of climate change,” said Hand in Hand Eastern Africa CEO Pauline Ngari. “Now more than ever, adaptation and mitigation are absolutely crucial. We thank the IKEA Foundation for playing their part, and enabling us to play ours.”

Entrepreneurship Clubs

Students in the Entrepreneurship Club at Wangu Primary School, Nairobi.

Empowering mothers to work their way out of poverty is a prerequisite to achieving the first Sustainable Development Goal, to ‘end poverty in all its forms everywhere’. But it raises an important question: if our members received entrepreneurship education earlier in life, would they be struggling as much to begin with?

Thanks to Hand in Hand’s Entrepreneurship Clubs, we’ll soon find out. The after-school clubs teach students aged 10 to 16 the basics of business, culminating in income-generating group projects used to offset participants’ school fees. In a country where high school graduates vastly outnumber available jobs, and where 80 percent of unemployed people are between the ages of 15 and 34, promoting entrepreneurship at school must be part of the solution.

By the numbers

43,200 jobs created

4,800 students in Entrepreneurship Clubs

US $3.6 million donated by the IKEA Foundation

Hand in Hand Youth Award winners visit Sweden

When Nelson Mureithi started farming eco-resilient trees, the 17-year-old from Mumbuini, Kenya never expected his business would take him outside his home county – much less 4,000 miles away to the shores of northern Europe.

But sure enough, Nelson was among the winners of Hand in Hand Eastern Africa’s inaugural Youth Award, who visited Sweden in May. The four winners, aged 15 to 19, met with local students and attended the Young Enterprise Trade Fair in Stockholm to swap business ideas with Sweden’s most promising young entrepreneurs.

Both the awards and the winners’ trip were generously sponsored by the Swedish Postcode Lottery. The competition is part of a three-year, US $1 million program designed to train 7,000 young Kenyans in entrepreneurship in after-school clubs.

Here, in brief, are the winners’ stories.

Solo Hayes Frank | 15 years old | Pharmaceutical sales

Prescription drugs aren’t always easy to come by in Kenya. Trips to numerous pharmacies are almost guaranteed – but not if Solo gets his way. Although he’s still in school, Solo envisions an online system that keeps track of which pharmacies have which drugs in stock. Hand in Hand is working to help him realise his vision.

Francis Mundia | 17 years old | Egg seller

Francis buys eggs from a local farm and sells them at a small margin. So far, so normal. But where his competitors are beholden to setting up stands at the local market, Francis has taken his business digital: customers visit his Facebook page and place orders online before Francis delivers them to their homes.

Nelson Mureithi | 17 years old | Eco-resilient-tree farmer

Sustainability and eco-resilience are more than just buzzwords; they’re a vital component of any agricultural strategy. That’s why Nelson has had such success growing and selling seedlings for multiple varieties of eco-resilient tree, counting some of the biggest farms in his area among his customers.

Evelyn Kinyua | 19 years old | Dove breeder

Doves, in Kenya, are a versatile product. Some of Evelyn’s customers eat them, but most keep them as pets, particularly during school holidays. Evelyn decided to breed doves when she realised most of her neighbours rear chickens. In a crowded market, standing out pays off.