Covid-19 updates

This page is no longer being updated. For the latest on Hand in Hand’s coronavirus response, click here.

Covid-19 has arrived in Hand in Hand’s countries of operation. Here, we provide updates on how we’re responding.

For information about how you can reduce your risk of infection, visit the World Health Organization website.

And to read a message from Hand in Hand International Chair Bruce Grant, click here.

Key updates

-

Teams in Afghanistan join fight against virus

-

Teams in Kenya join emergency response

-

Staff in Tanzania relay health information to members via mobile phone

Afghanistan

Hand in Hand is delivering soap, chlorine solution and crucial virus prevention training to 26,000 Afghans as part of the country’s official response to Covid-19 – with plans to reach 70,000 more.

The new project comes after a government lockdown in late-March banned gatherings of all kinds. In response, our usual business and skills training was suspended until 30 April – a date we’re keeping under constant review.

Afghanistan recorded its first confirmed case of Covid-19 on 24 February. Within weeks, Hand in Hand trainers were instructing members – many living in remote areas that public health messages don’t always reach – on virus prevention measures including handwashing, social distancing and more. Business and skills training continued during this time, with group meetings replaced by smaller home visits wherever possible. (For more on our initial response to Covid-19, click here.)

There are 1,092 confirmed cases of Covid-19 and 36 deaths in Afghanistan according to WHO figures, though the true number is expected to be many times higher. It’s also expected to keep rising as thousands of displaced Afghans cross the border every day from Iran, one of the hardest-hit countries in the world.

Kenya

In co-ordination with county governments, Hand in Hand is connecting with 86,000 members countrywide, providing support in two key areas: slowing/halting the spread of Covid-19 and ensuring food security for our members and their families.

With the country on lockdown, teams are trading Self-Help Groups for SMS’, motorbikes for mobile phones, reaching out to thousands of members individually to deliver key health messages (e.g. handwashing guidelines), signpost to vital health services, and counter fake news. At the same time, with food security a growing concern country- and indeed region-wide, they’re pointing agribusiness members towards alternative supply sources, signposting to Covid-19 relief opportunities such as soap-making and mask-making, and feeding back to government teams to identify communities in particular need. All this while restructuring repayment plans for members who’ve taken loans.

Behind the scenes, we’re ramping up efforts across several key projects, with work ongoing to: fully digitise our data from collection to analysis, allowing trainers to learn and adapt in real-time; develop the next generation Hand in Hand programmes, targeting alumni from previous projects for a second phase of higher income growth; and instruct staff on Hand in Hand Eastern Africa’s new training manuals, deepening our emphasis on women’s entrepreneurship.

Kenya recorded its first confirmed case of Covid-19 on 13 March. Two days later, local officials requested a pause on Hand in Hand group meetings as strict social distancing measures came into effect countrywide. Accordingly, and to play our part in halting the spread of the virus, Hand in Hand Eastern Africa temporarily suspended field activities until 1 July – a date we’re keeping under constant review.

There are 296 confirmed cases of Covid-19 and 14 deaths in Kenya, according to WHO figures.

Tanzania

Like in Kenya, staff in Tanzania are relaying virus prevention guidelines to rural, hard-to-reach members via mobile phone.

The country recorded its first confirmed case of Covid-19 on 16 March. Two days later, officials closed schools and suspended social gatherings. Accordingly, and to play our part in halting the spread of the virus, Hand in Hand’s team in Tanzania temporarily suspended field until 1 July – a date we’re keeping under constant review.

There are 255 confirmed cases of Covid-19 and 10 deaths in Tanzania, according to WHO figures.

Insights from Participatory Evaluation Processes: Adapting to Local Demands

This article previews Hand in Hand’s peer-learning session at the SEEP Annual Conference 2017. It first appeared on The SEEP Network blog

Your proposal was so scalable, it made USAID weep. Your logframe, so flawless it was exhibited at MoMA. Bono himself called to congratulate you on a “totally rockin’ independent baseline study”. But one year into program delivery, credit uptake is waning and dropout rates are creeping higher by the week.

What went wrong?

That’s the question new SEEP member Hand in Hand was forced to confront when two of our programs – one in Afghanistan, the other in Kenya – were threatened by similar issues. Despite more than 10 years’ experience training Savings Groups members how to launch their own microenterprises – resulting in more than 3 million new and improved jobs – we found ourselves humbled by an inescapable truth: nothing gets in the way of a masterfully designed program quite like reality. Adaptive management isn’t merely crucial to success – it’s necessary to survive.

This blog, and our session at the 2017 SEEP Annual Conference – ‘Insights from Participatory Evaluation Processes: Adapting to Local Demands’ on Tuesday, October 3 at 2:15pm – ponders a central element of adaptive management: feedback. In doing so, it posits a package of feedback mechanisms that can be (more or less) universally applied to produce useful learning, drawing on examples from the aforementioned cases, plus a third from VisionFund in Tanzania.

The learning that these mechanisms produced varied across contexts, but in each case the results were transformative, compelling Hand in Hand to redesign its theory of change and exit strategies in Afghanistan and Kenya respectively. Meanwhile in Tanzania, VisionFund applied a similar package of mechanisms during its pilot phase, and shares its experience of taking learning to scale.

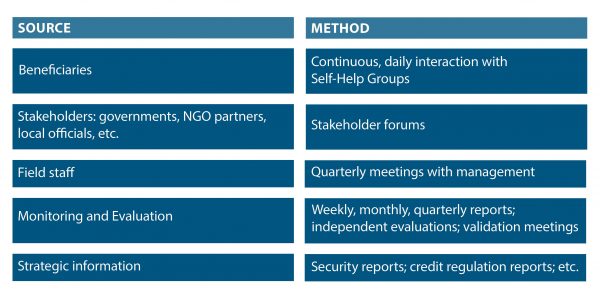

The Big Five: Feedback Mechanisms for Useful Learning

Feedback is only as good as the sources that provide it. In order to obtain the fullest picture possible, our package of mechanisms draws on the following sources and methods:

Each of the following cases employed our package of mechanisms. All have been edited for brevity. For the full picture, please attend our session on October 3.

Case One: Hand in Hand, Afghanistan

Occasionally, sources of feedback are in perfect harmony. Such was the case for Hand in Hand Afghanistan, who administered an Enterprise Incubation Fund (EIF) to finance members’ microenterprises where other institutions wouldn’t. Increasing numbers of beneficiaries said they were loath to take loans in remote rural areas where the Taliban had identified credit programs as an opportunity to disrupt NGO activity, branding them as a Western imposition. M&E data showing reduced uptake confirmed their waning interest. Other NGOs had by and large abandoned cost-recovery models in favor of flat-out grants, rendering microfinance even more unattractive. Field staff reported difficulties in recovering loans (and in some cases received anonymous threats). And strategic information pointing to a resurgent Taliban provided scant hope Afghanistan’s credit environment would improve anytime soon.

With all sources of feedback pointing in the same direction – decisively away from our microfinance component – Hand in Hand closed the EIF, adopting productive asset transfer in its place. In the time since, we have distributed some 21,300 Enterprise Startup Toolkits containing all the necessary inputs to launch a business in nine accessible, high-margin sectors such as beekeeping and tailoring, designed to maintain the self-help ethos that lay behind the credit component. Feedback has again been unanimous – this time in our favor.

Case Two: Hand in Hand, Kenya

Things would not be so straightforward in Kenya, where Hand in Hand’s EIF faced the opposite problem: it was too popular. Prior to October 2016, we provided three cycles of subsidized microcredit to members. Not surprisingly, beneficiaries were happy to continue borrowing at slightly below-market rates. But field staff complained they were overworked – tied to old members by cycle after cycle of credit while juggling ambitious recruitment targets for new members. The M&E data agreed: recruitment was indeed slowing down. Strategic information meanwhile pointed to a robust ecosystem of local MFIs, suggesting credit was available from other institutions.

Staff and management met in September, 2016 and immediately embarked on a set of program reforms, reducing the number of loan cycles from three to one. A 27-month phase-out strategy was also agreed, whereby groups would receive nine months of intensive training, 12 months for the EIF credit cycle, and six months of support on market linkages for commodities and loans. Finally, it was agreed that after 27 months, we would help mobilise members into co-operatives known as Community-Based Organisations that would help them lend to each other and gain access to bigger markets and value chains.

Initial feedback suggests the changeover is working favorably.

Case Three: VisionFund, Tanzania

From October 2016 until August 2017, VisionFund Tanzania, World Vision Tanzania and private sector grower/exporter the Great African Food Company (GAFCo) partnered to run seven pilots in different regions of Tanzania with more 3,000 smallholder sunflower and kidney bean farmers. The goal was to improve these beneficiaries’ outputs and, ultimately, their livelihoods.

Involving technology, crop insurance, loan credit processes, payment to farmers, and beneficiary engagement and education, the pilot was highly complex, and field staff reported challenges testing so many combined elements in a variety of locations. But partners had identified both a need and an opportunity: GAFCo needed to generate and test volume and quality for its European buyers, and there was an opportunity to test the approach in parallel across regions.

A major review took place in July 2017, following a review process experiment in June. Senior management from the three partners met with beneficiaries and external stakeholders, including village elders and local and regional government, as part of a 10-day M&E trip visiting each of the pilot locations and engaging in detailed conversations. The process resulted in identifying improvements in beneficiary education, explaining better to village authorities the detail behind areas such as crop insurance, and generating buy-in from local officials.

The model has now been adapted for a wider rollout from October, with an ongoing monitoring of the engagement with beneficiaries and other stakeholders to test the scalability and acceptability of the updated model and improvements in client training.

Hand in Hand creates 3 millionth job

Fourteen years ago, Percy Barnevik and Dr Kalpana Sankar joined forces to expand a small charity in southern India that provided free schooling to children working in the local silk trade. It was called Hand in Hand.

They soon realised the real problem wasn’t a lack of schools; it was the desperation that forced parents to send their children to the factories in the first place. “We had to attack the root cause of the problem: poverty,” says Barnevik.

Fast-forward to today and that’s exactly what Hand in Hand has done, fighting poverty with business and skills training from Afghanistan to Zimbabwe and in eight countries in between. Today, we’re proud to announce a major milestone in our story: the creation of Hand in Hand’s 3 millionth job.

“Even when they’re undernourished, downtrodden and illiterate, Hand in Hand’s entrepreneurs have an enormous will,” says Barnevik, now Hand in Hand’s honorary chair. “When they get a chance they’re not letting it go by. These women can move mountains.”

Here’s to fourteen more years, millions more jobs and more moved mountains.

Hand in Hand must ‘prioritise income diversification’ in Tanzania: study

Hand in Hand’s programme in Tanzania will hinge on two key factors, according to a new report from Ipsos: changing the way people think about Self-Help Groups and helping our members diversify their incomes.

Published this month, the report surveyed 4,000 adults in Arusha and Kilimanjaro, providing Hand’s in Hand’s clearest picture yet of life in our target areas and establishing the baseline by which future progress will be measured. With the report finished, group mobilisation can begin later this year.

Our target districts

There is no shortage of districts in Tanzania that could benefit from Hand in Hand’s training. To begin with, we’re focusing on five: Ashura Rural and Meru in Aruha, and Moshi Rural, Hai and Rombo in Kilimanjaro. Besides their proximity to our headquarters in Kenya, the districts were chosen because each has a population density of at least 150 people per square kilometre, the minimum required to make our programme viable according to Ipsos.

More than half of Arushans (55 percent) and one-third of Kilimajarans (34 percent) live in poverty, according to the UNDP 2014 Human Development Report. Across our target districts, the estimated rural adult population living in poverty is 293,110. If Hand in Hand achieves our goal, a significant majority (68 percent) of impoverished adults in our target areas will see their lives transformed.

By the numbers

Rural adult population living in poverty in Hand in Hand’s target areas: 293,110

Number of jobs we aim to create: 200,000

Percentage of target rural poor with improved incomes: 68 percent

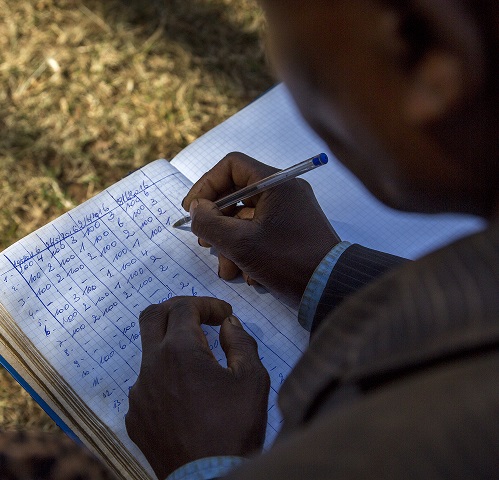

Before we can start to mobilise in earnest, we need to know everything we can about our future members. What are their livelihoods? How can we help them most effectively? What threats do they most consistently face? Only 9 percent of households surveyed by Ipsos earned their income solely from business – owning a shop, say, or transporting people and goods on motorcycles (known in Eastern Africa as boda boda). An additional 15 percent earned a portion of their income from business. The rest, 76 percent, relied entirely on farming to see them through, many at the subsistence level. It’s no surprise, then, that only 57 percent of respondents are putting money aside as savings. Perhaps more surprising was the degree of organisation among those surveyed: 34 percent of respondents already belong to Self-Help Groups. The groups exist chiefly to support members in times of trouble (46 percent) and occasionally as a source of microfinance (20 percent), and are registered with local government.

Challenges

There are two seasons in northern Tanzania: rainy and dry. For the 91 percent of adults who rely on agriculture for some or all of their incomes, says Ipsos, the resulting boom-and-bust crop cycle means periods of relative abundance followed by periods of scarcity and hunger.

Making matters worse, ‘rainy’ and ‘dry’ can often mean ‘flooding’ and ‘drought’, and depressed incomes and food insecurity are perennial risks. In an environment where almost half of households (43 percent) regard saving as an impossibility, “fear and mistrust” of savings-driven Self-Help Groups are common, warns the report. Microfinance is considered even more dangerous and avoided for fears that climatic shocks will wipe out crops and livestock, leading to borrowers to default on their loans.

Recommendations

Hand in Hand group savings meeting, Rwanda

Only 5 percent of survey respondents who belonged to pre-existing groups said they were being supported by NGOs. To begin with, says the report, Hand in Hand should focus on the other 95 percent, filling gaps in skills training, the provision of microfinance and links to larger markets. Mobilising the ‘un-grouped’ – the 66 percent majority who worry they cannot save – will require a softer touch, says Ipsos. Here, initial efforts should focus on “community sensitisation… to change negative perceptions”, and “may require a pull factor, e.g. market linkages, to bring people together.” It will also require a programme that addresses climatic shocks head-on, reducing risk in order to incentivise savings and credit. This “can be achieved through Hand in Hand’s entrepreneurship training” in two ways, Ipsos concludes. For starters, early training modules should promote farming practices that mitigate the effects of climate change: irrigation, planting trees to reduce soil erosion and so on. Secondly, once groups are firmly established, training should “prioritise income diversification” and encourage members to launch businesses that generate income all year.

Download the reportTanzania expansion: founding donation received

Hand in Hand is on track to create 200,000 sustainable jobs in Tanzania over the next five years, thanks to a founding donation of approximately US $1.5 million.

Received this month, the funds will support in full the first phase of Hand in Hand Eastern Africa’s expansion into the country. That phase, expected to last a year, will see:

- Our job creation model adapted for the Tanzanian context;

- Offices established in Arusha and Moshi;

- Staff hired;

- Contracts signed with partner organisations to help scale up the programme.

By the numbers

The donation will also help kick off our Tanzanian operation’s second phase, unfolding between 2017 and 2021. By the time Phase Two is done, we’ll have created:

150,000 sustainable businesses

200,000 jobs

30% average increase in household income

750,000 transformed lives

Why Tanzania

Two-thirds of Tanzanians live in poverty, according to the United Nations Development Programme. Almost half, 44 percent, live on less than US $1.25 a day. Promisingly, annual GDP growth hovers at close to 7 percent. It’s a welcome trend, if one that belies reality for the country’s mostly rural population: the poorest 20 percent of Tanzanians own less than a tenth of the country’s wealth.

Starting a formal business in Tanzania is difficult and getting harder all the time. The country dropped seven places to 129th overall in the World Bank’s 2016 Doing Business report, which measures business regulation in 189 countries. Now more than ever, family entrepreneurs in the informal economy must pick up the slack.

For more information about Hand in Hand’s expansion into Tanzania, please contact Dorothea Arndt.

Hand in Hand expands into Tanzania

Hand in Hand is expanding into Tanzania.

Launching in April 2016, our operation in Arusha – a city of 400,000 in the shadow of Mount Kilimanjaro – will be supported by staff from Hand in Hand Eastern Africa’s Nairobi headquarters. The location was chosen for its proximity to Kenya, and because our needs analysis shows the area will benefit most from our work.

For the first year, we’ll be laying the groundwork for further expansion in the country. In the second year, we’ll begin to make a significant impact. The search for strategic partners in Tanzania, selected to help scale up our operations in a similar manner to CARE Rwanda, is underway now.

“A quarter-million entrepreneurs have seen what our model can do in Kenya and, more recently, Rwanda,” said Hand in Hand International CEO Josefine Lindänge. “Expanding into Tanzania is a logical next step for our team in Eastern Africa.”

Two-thirds of Tanzanians live in poverty, according to the United Nations Development Programme. Almost half, 44 percent, live on less than US $1.25 a day. Promisingly, annual GDP growth hovers at close to 7 percent. It’s a welcome trend, if one that belies reality for the country’s mostly rural population: the poorest 20 percent of Tanzanians own less than a tenth of the country’s wealth.

Starting a formal business in Tanzania is difficult and getting harder all the time. The country dropped seven places to 129th overall in the World Bank’s 2016 Doing Business report, which measures business regulation in 189 countries. Now more than ever, family entrepreneurs in the informal economy must pick up the slack.

Best Practice: Jeremy Lefroy MP

Welcome to Best Practice, our occasional series of Q&As with leaders in the field of international development. In this, our first instalment, we speak to Equity for Africa (EFA) Co-Founder and Conservative MP Jeremy Lefroy.

Lefroy co-founded EFA in 2003 after spending 11 years in Tanzania – where he worked with the local coffee industry – to provide lease finance to agricultural enterprises too small for banks and too big for micro-lenders. He joined parliament’s International Development Committee in 2010, having been elected to represent Stafford that same year, and has helped manage the policy, expenditure and administration of the Department for International Development (DFID) ever since.

What are the biggest challenges in development right now?

That’s a very big question – I’ll give you a few. One is increasing income inequality, alongside the fact that we still have over a billion unbelievably poor people. The World Bank has two main objectives: to abolish extreme poverty by 2030, which I welcome, and to concentrate on the bottom 40 percent of the income spectrum in order to try and reduce extreme inequalities of income. The idea is to lift everybody while at the same time trying to reduce the gap. That’s fundamental, because it’s not only extreme poverty but extreme inequality that drives potential social instability, along with many other things.

Next I would say education. There’s been a great improvement in access to primary education over the last 20 years, but there hasn’t been such an improvement in access to secondary, and certainly not to tertiary education, where people acquire the skills that are going to enable them to improve their life chances. At the same time, there are concerns about the quality of education, even at the primary level. In quantity it has increased, but in quality there are question marks.

That brings me to the third point: in almost every professional area, particularly in healthcare and education, we’re very, very lacking in skills. Just take the UK, where we’re going to run short of GPs in the next few years. What’s going to happen? Inevitably, we’ll simply buy them from overseas, which will reduce the available pool there. There’s a massive looming skills shortage in everything from health and education to engineering and other technical subjects.

Then, of course, there’s the challenge of resources. The impact of climate change – the need to adapt and mitigate – will be particularly felt around water and consequentially food. We also need resources in terms of power generation, especially in the context of a rising population. I’ve never been a person who believes a rising population is inherently problematic, but there comes a point where if it doesn’t flatten out at about 9 billion we’re going to have some serious problems.

Your not-for-profit, Equity for Africa, helps grow small- and medium-sized agricultural enterprises in Tanzania by providing lease finance for equipment, among other things. It’s a model that’s not too far from Hand in Hand’s, and certainly one that’s informed by the same ethos of ‘help to self-help’.

It tends to be that 90 percent of jobs in developing countries are created by the private sector. Beyond that, becoming an entrepreneur by its very nature improves your education: you have to learn about other things, you have to be literate and, usually, you have to be numerate. You have to learn these skills to survive in business that you might not have learnt in the education system.

One of the main inequalities, of course, is gender inequality. And helping the private sector, helping people through mentoring and finance, has a disproportionately beneficial effect on women, who tend to be better entrepreneurs and better at managing their finances. And of course there’s the connection between jobs and security.

Definitely. Jobs, for me, are essential. When my friends and I set up Equity for Africa, it was all around jobs – that was the focus. We wanted to see as many jobs created as possible for as low an investment as possible, but they had to be sustainable, and I think we’ve made a reasonable start. By their very nature, jobs improve your household income. They give you an investment for the future. They give you dignity and self-respect, assuming you’re being treated in a reasonable way by your employer. They generally have a positive impact on your health. And they help bring stability. If you’re desperate and the only money on the table is from, say, the Taliban, it takes a very strong and very principled person to turn that down when the alternative is not having any way to feed your family.

What compelled you to start Equity for Africa?

Complete failure. I’d started a programne with some friends in the mid-’90s called Training for Life, which was there to help Tanzanian school leavers, who were entering a very poor job market, learn life skills that weren’t taught in school. We wanted to give them hope. That programme is still running nearly 20 years on – we’ve had hundreds of young people go through with it, many now working in senior positions. But what didn’t work so well was a loan scheme I’d set up, and funded, to give trainees an opportunity to obtain capital they couldn’t get through a bank. I was probably naïve in the way I approached it, and very few of the loans were repaid – not because of mismanagement and fraud but because we simply hadn’t put enough effort into going through the business plans.

I’d obviously approached it in totally the wrong way, but I still felt it was very important to finance businesses that were too big for microfinance and too small for banks, so a few years later I had another go. This time I went in with a friend of mine, Michael Timmerman, who’s an expert and he was able to guide us in the right direction: a more rigorous approach that combined, if you like, my entrepreneurial enthusiasm with Michael’s ability to look at business plans to say “this will work and this won’t work”, adjust them and occasionally turn them down. We’ve since managed to get a (US) $5 million fund together and increase the amount of money available for each investments. We approved about 45 investments under the new, larger funds over the course of about a year, and that’s increasing all the time.