Insights from Participatory Evaluation Processes: Adapting to Local Demands

02 Oct 2017

A Hand in Hand Self-Help Group in Rwanda

This article previews Hand in Hand’s peer-learning session at the SEEP Annual Conference 2017. It first appeared on The SEEP Network blog

Your proposal was so scalable, it made USAID weep. Your logframe, so flawless it was exhibited at MoMA. Bono himself called to congratulate you on a “totally rockin’ independent baseline study”. But one year into program delivery, credit uptake is waning and dropout rates are creeping higher by the week.

What went wrong?

That’s the question new SEEP member Hand in Hand was forced to confront when two of our programs – one in Afghanistan, the other in Kenya – were threatened by similar issues. Despite more than 10 years’ experience training Savings Groups members how to launch their own microenterprises – resulting in more than 3 million new and improved jobs – we found ourselves humbled by an inescapable truth: nothing gets in the way of a masterfully designed program quite like reality. Adaptive management isn’t merely crucial to success – it’s necessary to survive.

This blog, and our session at the 2017 SEEP Annual Conference – ‘Insights from Participatory Evaluation Processes: Adapting to Local Demands’ on Tuesday, October 3 at 2:15pm – ponders a central element of adaptive management: feedback. In doing so, it posits a package of feedback mechanisms that can be (more or less) universally applied to produce useful learning, drawing on examples from the aforementioned cases, plus a third from VisionFund in Tanzania.

The learning that these mechanisms produced varied across contexts, but in each case the results were transformative, compelling Hand in Hand to redesign its theory of change and exit strategies in Afghanistan and Kenya respectively. Meanwhile in Tanzania, VisionFund applied a similar package of mechanisms during its pilot phase, and shares its experience of taking learning to scale.

The Big Five: Feedback Mechanisms for Useful Learning

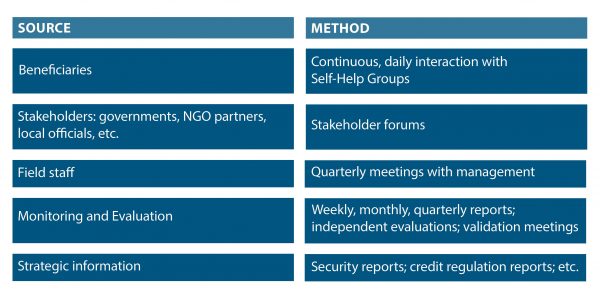

Feedback is only as good as the sources that provide it. In order to obtain the fullest picture possible, our package of mechanisms draws on the following sources and methods:

Each of the following cases employed our package of mechanisms. All have been edited for brevity. For the full picture, please attend our session on October 3.

Case One: Hand in Hand, Afghanistan

Occasionally, sources of feedback are in perfect harmony. Such was the case for Hand in Hand Afghanistan, who administered an Enterprise Incubation Fund (EIF) to finance members’ microenterprises where other institutions wouldn’t. Increasing numbers of beneficiaries said they were loath to take loans in remote rural areas where the Taliban had identified credit programs as an opportunity to disrupt NGO activity, branding them as a Western imposition. M&E data showing reduced uptake confirmed their waning interest. Other NGOs had by and large abandoned cost-recovery models in favor of flat-out grants, rendering microfinance even more unattractive. Field staff reported difficulties in recovering loans (and in some cases received anonymous threats). And strategic information pointing to a resurgent Taliban provided scant hope Afghanistan’s credit environment would improve anytime soon.

With all sources of feedback pointing in the same direction – decisively away from our microfinance component – Hand in Hand closed the EIF, adopting productive asset transfer in its place. In the time since, we have distributed some 21,300 Enterprise Startup Toolkits containing all the necessary inputs to launch a business in nine accessible, high-margin sectors such as beekeeping and tailoring, designed to maintain the self-help ethos that lay behind the credit component. Feedback has again been unanimous – this time in our favor.

Case Two: Hand in Hand, Kenya

Things would not be so straightforward in Kenya, where Hand in Hand’s EIF faced the opposite problem: it was too popular. Prior to October 2016, we provided three cycles of subsidized microcredit to members. Not surprisingly, beneficiaries were happy to continue borrowing at slightly below-market rates. But field staff complained they were overworked – tied to old members by cycle after cycle of credit while juggling ambitious recruitment targets for new members. The M&E data agreed: recruitment was indeed slowing down. Strategic information meanwhile pointed to a robust ecosystem of local MFIs, suggesting credit was available from other institutions.

Staff and management met in September, 2016 and immediately embarked on a set of program reforms, reducing the number of loan cycles from three to one. A 27-month phase-out strategy was also agreed, whereby groups would receive nine months of intensive training, 12 months for the EIF credit cycle, and six months of support on market linkages for commodities and loans. Finally, it was agreed that after 27 months, we would help mobilise members into co-operatives known as Community-Based Organisations that would help them lend to each other and gain access to bigger markets and value chains.

Initial feedback suggests the changeover is working favorably.

Case Three: VisionFund, Tanzania

From October 2016 until August 2017, VisionFund Tanzania, World Vision Tanzania and private sector grower/exporter the Great African Food Company (GAFCo) partnered to run seven pilots in different regions of Tanzania with more 3,000 smallholder sunflower and kidney bean farmers. The goal was to improve these beneficiaries’ outputs and, ultimately, their livelihoods.

Involving technology, crop insurance, loan credit processes, payment to farmers, and beneficiary engagement and education, the pilot was highly complex, and field staff reported challenges testing so many combined elements in a variety of locations. But partners had identified both a need and an opportunity: GAFCo needed to generate and test volume and quality for its European buyers, and there was an opportunity to test the approach in parallel across regions.

A major review took place in July 2017, following a review process experiment in June. Senior management from the three partners met with beneficiaries and external stakeholders, including village elders and local and regional government, as part of a 10-day M&E trip visiting each of the pilot locations and engaging in detailed conversations. The process resulted in identifying improvements in beneficiary education, explaining better to village authorities the detail behind areas such as crop insurance, and generating buy-in from local officials.

The model has now been adapted for a wider rollout from October, with an ongoing monitoring of the engagement with beneficiaries and other stakeholders to test the scalability and acceptability of the updated model and improvements in client training.